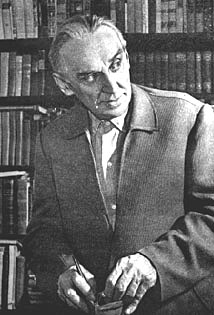

Fedin, Konstantin Aleksandrovich. Born 24 February (12 February, Old Style) 1892 in Saratov. His father was a merchant, running a stationary store. At a young age, in addition to attending school, Fedin began to learn the violin. In 1901, he entered the Commercial Academy. In 1905, together with his entire class, he participated in a student's strike. In 1907, he ran off to Moscow where he pawned his violin. His father, however, tracked him down and dragged him home. He made another attempt to escape--in a boat along the Volga--but this plot was foiled, too.

Fedin, Konstantin Aleksandrovich. Born 24 February (12 February, Old Style) 1892 in Saratov. His father was a merchant, running a stationary store. At a young age, in addition to attending school, Fedin began to learn the violin. In 1901, he entered the Commercial Academy. In 1905, together with his entire class, he participated in a student's strike. In 1907, he ran off to Moscow where he pawned his violin. His father, however, tracked him down and dragged him home. He made another attempt to escape--in a boat along the Volga--but this plot was foiled, too.

Rather then go to work in his father's store, Fedin continued his studies at the Commercial Academy in Kozlov. It was here that he developed a love of literature and started writing. His first story, written in 1910, was Sluchai c Vasiliem Porfirevich ("Incident with Vasili Porfirevich"), an imitation of Gogol's Overcoat.

In 1911, he went on to study economics at the Moscow Commercial Institute. He continued writing and in 1913 his first published work, Melochi ("Trifles") appeared in the Petersburg journal New Satirycon. Upon seeing his words in print for the first time, Fedin recalls being so happy that he skipped and sang.

In the spring of 1914 he went to Nuremburg to study German. At the outbreak of World War I, he tried to high-tail it back to Russia, but he seized in Dresdan. He and other Russians were held by the Germans as civilian hostages until the conclusion of the Brest Treaty. So, in the autumn of 1918 Fedin returned to Moscow, where he worked for a while in the People's Commisariate of Education.

In 1919, Fedin moved to the town of Syzran, where he worked as editor and writer for the newspaper Syzran Communar. He didn't stay there for long, however. In the autumn of 1919 he was mobilized and sent to the Petrograd front during Yudenich's attack. He was assigned first to a calvary division, then transfered to serve as assistant editor of the paper Fighting Pravda. From 1921 to 1924, he served as editor of the magazine Books and Revolution. During this time, he continued writing articles and stories and was closely associated with the Serapion Brothers, a literary goup dedicated to the inividual freedom of the creative act. Later Soviet critics were hostile to the Serapion Brothers, and Fedin tried to distance himself from the group, saying he saw the need to break with them thanks to the

influence of Maksim Gorky. Fedin wrote:

After meeting Gorky, I can't explain what was happening with me. In my soul, I recited an unending monologue. This was a feeling of liberation. It seemed that I had broken out of a narrow, almost impassable confine onto a vast open space; that now was the time to scratch away the scabs of the past, to purifiy myself; that I had won a special right to creation--of course, pure, real creation; that I would have to defend this right, but that I, of course, would defend it because my helpmate was Gorky. Yes, I mentally called him this: my helpmate and liberator.

In assessing the work of Fedin at the time, Maksim Gorky wrote:

Konstantin Fedin is a serious and intense writer, who works carefully. He is one of those who does not hurry to speak, but who knows how to speak well.

Fedin's first collection, Pustyr ("Wasteland") appeared in 1923. It included the story Sad (Orchard), the tale of an old gardener who watches sadly as the orchard he cared for and the manor house of the old owners are turned over to a Soviet orphanage and fall into neglect. In the end, the gardener sets the house and orchard on fire. This work won Fedin the first prize from the House of Writers.

In 1924, Fedin finished his masterful novel Goroda i Gody ("Cities and Years"), one of the first Soviet novels, portraying the path of the intelligentisa during the Revolution and Civil War. It was also a work of stylistic and structural novelties. In the novel, a spineless Russian intellectual, Andrei Startsov, is interred in Germany at the start of World War I. He falls in love with a German girl, Mari, who helps him in an escape attempt. He is perceptive in his observations of the cruelty and contradictions of German militarism, and back in Russia after the war, he struggles to find his place in Revolutionary society. He wants to join the new exciting world, but is frozen by his intellectual detachment and proves unable to make any contribution, to take any action. He was, in short:

...a man who, with anguish, waited for life to accept him. To his very last moment, he took not a single step, but waited for the wind to bring him to the shore he hoped to reach.

Forgetting his promises to send for Mari, Andrei drifts into another affair and gets another girl pregnant. He also helps a personal acquaintance, now a counterrevolutionary, escape Soviet justice. He has a chance to turn in this enemy of the people, but fearing that he himself would have a man's blood--even a guilty man's blood--on his hand, he fails to take action. For this betrayal of the Soviet cause, his best friend kills Andrei.

Fedin called Cities and Years an "emotional sequence" and told it with a non-sequential narrative line, starting with the end. If arranged in the proper time sequence, the order of chapters would be: 4, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 2, 9, and 1. The novel is also filled with frequent lyrical digressions.

In the 1930s, the German translation of Cities and Years had the honor of being among those books burned on Nazi bonfires.

In 1926, Fedin retired to a village in the Smolensk region. There he wrote Transvaal, the story of a cruel Estonian of Boer extraction who comes to wield almost dicatorial power over the peasants of his village. Some critics disliked the story, seeing in it a defense of kulaks.

Fedin's next novel, Bratya ("Brothers"), appeared in 1928. This novel--again employing temporal displacements--is the story of musician and composer who attempts to claim an expemption from Revolutionary service in pursuit of his individual artistic expression. He argues with his brother, a Bolshevik who goes off to die in battle. In the end, the musician takes up his brother's cause and believes, therefore, that he has overcome the contradiction between art and Revolutionary activity. However, his view of art as essentially tragic, born in solitude, remains unchanged.

In that same year, Fedin traveled through Norway, Holland, Denmark, and Germany. Then, in 1931, he fell ill with pulmonary tuberculosis and went to Switzerland for treatment. He then spent the years 1933 and 1934 in Italy and France. These trips provided material for his next two novels, Pokhishcheniye Evropy ("The Rape of Europe") (1934) and Sanatori Arktur ("The Arktur Sanitorium") (1940). In The Rape of Europe, members of a bourgeois Dutch family bicker among themselves as they try to hold onto a timber concession in the Soviet Union. In the end, the Soviet Union is strong enough to kick them out, reducing them to the status of timber brokers. The tale is told through the eyes of a Communist journalist, who abscounds with the wife of one of the Dutchmen. The Arktur Sanitorium depicts patients in a Swiss health sanitorium.

In 1934, Fedin was elected to the board of the Writer's Union. During World War II, he worked as a war correspondent, but also found time to produce the play Ispytaniye Chuvstv ("Test of Feelings") (1942). This play depicts a heroine, Aglaia, involved with the anti-German resistance.

Fedin turned his pen to a book of literary reminiscences, Gorky Sredi Nas (Gorky Among Us), the first volume of which was published in 1943. It was of great literary interest and highly praised. The second volume, released in 1944, however, did not fare so well. Containg portraits of writers such as Sologub, Remizov, Volynsky, and others, the work was criticized for being "objective" and "dispassionate", of having ignored the historical-political background. Fedin was accused of a "revaluation of values". Marietta Shaginyan said he showed a "soft benevolence" and engaged in a "distortion of the

past". Tikhonov faulted Fedin for misinterpreting Gorky's position. As a result, this volume was withdrawn from circulation.

Fedin returned to novels and undertook a triology consisting of Perviye Radosti ("First Joys") (1946), Neobyknovennoye Leto ("No Ordinary Summer") (1948), and Koster ("The Bonfire") (1961), offering a chronicle of Russian life between 1910 and 1941. The first of these, First Joys, is a broad, realistic novel set in Saratov on the Volga on the eve of World War I. It shows the actions of a young, budding revolutionary (Izvekov) and an older revolutionary factory worker (Ragozin), as well as various other strata of pre-revolutionary Russia. No Ordinary Summer begins in 1919 when a Russian soldier escapes from a German prisoner of war camp and makes it back to Russia, which is caught up in the Civil War. Also returning are Izvekov and Ragozin, who meet up with old friends and

enemies. As Aleksei Tolstoy did in his novel Bread, here Fedin alters history somewhat to make Stalin, not Trotsky, the hero of the Battle of Tsaritsyn. The novel also features a nonpolitical writer trying to maintain his artistic freedom and express his sympathies for the suffering, no matter what side they are on. And in the third book of the trilogy, The Bonfire, a positive hero rushes to the defense of the motherland when the Nazis invade Russia.

In commenting on The Bonfire, Fedin noted that, throughout his career, he strove to not only to create characters who were, in their own way, heroes of their time, but also to protray the character of that time itself. He wrote:

My constant goal has been to find the image of the time and to include the time in the narrative on equal footing with, and even given preference over the heroes of the story.

Elsewhere, he summed up the duty of a writer:

Not to simplify the process of social development, of the life of the people, but to disclose life in all its complexity and so delineate and affirm the foundation on which the future shall be built--such is the duty of the artist.

Fedin produced some portraits of his friends and contemporaries in Pisatel, Iskusstvo, Vremya ("Writer, Art, Time") (1957). He received two Stalin Prizes, in 1948 and in 1950. He served as head of the Soviet Writers Union from 1959 to 1971 and, in this capacity, denied publication to Solzhenitsyn's Cancer Ward in 1968. From 1971 until 1977 Fedin worked on the editorial board of Novy Mir. He was married and had one daughter.

Konstantin Fedin died in Moscow on 15 July 1977.

See also: Fedin on the State of Soviet Literature, 1957.

References: Russian Writers and Poets. Short Biographical Dictionary. Moscow, 2000.

|

|