presents

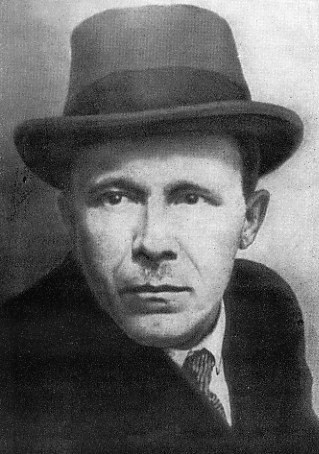

Neverov, Aleksandr Sergeevich. Born 12 December 1886 to a family of peasant workers in the village of Novikovko in the Samara guberniya. His real family name is Skobelev. Due to the early death of his mother and the fact that he father (a drunkard) left the family to marry another woman, the young Neverov and his four siblings grew up in the house of his grandfather, a small shopkeeper.

Neverov, Aleksandr Sergeevich. Born 12 December 1886 to a family of peasant workers in the village of Novikovko in the Samara guberniya. His real family name is Skobelev. Due to the early death of his mother and the fact that he father (a drunkard) left the family to marry another woman, the young Neverov and his four siblings grew up in the house of his grandfather, a small shopkeeper.At age 15, Neverov went to work in a typography shop. At first he enjoyed the work, but soon got bored with the monotony and quit. His grandfather found him a job in a haberdashery, but again Neverov quit. For a third time, Neverov's frustrated grandfather placed the youth in a job--in a textile shop. This time Neverov (although he didn't like the job) stuck around for at least a year. During this time, Neverov began to scribble poetry. He showed some to a local self-taught poet named S.V. Denisov. It was obvious that Neverov's primitive education was limiting his poetic growth. (He didn't even know where to put commas.) So, in 1903, the teenager got himself admitted to the Ozerkovsky Secondary School on a scholarship. There was a heavy dose of religious instruction at this school, which seemed to irk Neverov. He peppered the priests with questions such as, "If God can do everything, can he create a stone so heavy that even he can't lift?" Reports on this irreverant behavior, of course, went on his permanent record. While at school, Neverov had his first exposure to political and revolutionary literature. During the Revolution of 1905, he was active in organizing student protests. In the spring of 1906, Neverov graduated from school and was sent to the village of Novy Pismer as a teacher. In March of that same year, Neverov's first story, Drowning Sorrow (Gore zalili) appeared in the Petersburg journal Vestnik trezvosti.

During his first year in Novy Pismer, Neverov penned various feuilletons protesting injustices suffered by the local peasants. Although he used the pen name of "Ivan Chervyak", Neverov was identified as the author and placed under secret police surveillance. Nothing ever came of the matter, and over the next nine years, Neverov lived in relative peace and quite, moving from village to village as a teacher. He continued to produce stories such as Coming to the Bazaar (Priekhali na bazar, 1907) and Old Woman Ivan Baba Ivan (1910). Old Woman Ivan is about a peasant woman who locks her drunken husband up in a barn and takes his place at a village meeting. The stories Grey Days (Seriye dni, 1910) and The Teacher Stroikin (Uchitel' Stroikin, 1911) describe the mind-numbing monotony endured by intelligent teachers living in the villages. An anti-alcholic cycle included the stories Under the Snowstorm's Song (Pod pecen' v'iuga, 1908) and Three Years (Tri goda, 1908). In 1912, Neverov married Pelagaya Andreevna Zelentsova, who was a teacher in a neighboring village. At the outbreak of World War I, Neverov was drafted into the army. He was trained as a medic and sent to work in an army hospital in Samara. He continued to write, producing From Unknown Reasons (Ot neizvestnikh prichin) and Vitul. In the former work, a woman becomes disenchanted with her priest husband, who has begun to cherish money. The latter story tells of a peasant's dream to get rich by making and selling illegal spirits. Neverov's stories came to the attention of Maksim Gorky, who sent the young writer several encouraging letters. Neverov greeted with revolution of February 1917 with a naive enthusiasm. He was elected to the Samara Soviet. He wrote a series of articles entitled Conversations With Peasants About Freedoms. The articles, which appeared in the newspaper Free Word (Svobodnoye slovo), basically were a defense of the positions taken by the Social-Revolutionary (S-R) Party. Through 1917 and 1918 Neverov worked as a journalist. Around this time, he also produced the story Cross on a Hill (Krest na gore), in which a coachman complains of the current situation as he drives a distracted intellectual around the Samara territory. In 1918, Neverov came down with typhus. The forces of Admiral Kolchak captured Samara in early December 1918. By the end of the year, the city was liberated by the Red Army. Neverov's conversion to Bolshevism--a process which had been underway for some time--was now complete. Declaring, "The people feel with their heart who is their friend and who is their enemy," Neverov went to work for the Bolshevik paper Forward (Veperyod). Continuing his journalistic work, Neverov also increased his literary production. The story Red Army Man Terekhin (Krasnoarmeets Terekhin, 1919) follows the positive transformation of the social conscience of a common Red Army soldier, from jealosy to pride in the common future of his fellow countrymen. In 1919-1920, Neverov authored several plays which met with critical acclaim. Women (Baby) won first prize at a Moscow competition for works about the peasantry. In the play, a soldier returning from the front and suffering a type of post-traumatic stress syndrome, torments his wife because of his suspicions about her fidelity, suspicions fanned by his own father. The 1921 story Marya the Bolshevik (Marya - Bolshevichka) tells the tale of a "new, liberated woman" in post-revolutionary Russia. In 1921, drought and famine hit the Samara region. To feed himself and his family, Neverov managed to organize a literary trip to Tashkent, where he could buy food. On the train trip to Tashkent, Neverov was greatly moved and distressed by the hordes of hungry children begging for crumbs at every station and by the sight of dead and dying bodies lying everywhere. In May of 1922, Neverov moved to Moscow. He was not immediately enamored of the literary circles he encountered there. Commenting on the various types he met in literary clubs and offices, he wrote in his diary: General impression: These people live on a different planet and are completely uninterested in anything which does not come forth from them themselves. The life of the country and the provinces is for them distant, foreign, and incomprehensible. They all rotate in a circle drawn by their own hands.However, he did meet with some like minds and found himself associated with the so-called Smithy group of writers. A meeting with Aleksandr Serafimovich and attendance at a reading of Serafimovich's Iron Flood, had a profound effect on Neverov. Later, Fyodor Gladkov recalled: For several days [after the evening at Serafimovich's] he, Neverov, experienced an agitation, you could even see a fever burning in his eyes. He wrote day and night, not tearing himself away from the typewritter.The first work Neverov completed in his Moscow period was the tale Andron the Good-for-Nothing (Andron Neputyovii, 1922). The hero of this tale is a soldier who returns to his home village and shocks everyone with his idea that everything in Russian should henceforth be done differently. Also in 1922 he penned an article on the creative work of Ivan Bunin, whose works had heavily influenced him in his earlier days. On 19 May 1923, Neverov completed his most famous tale, Tashkent - City of Bread (Tashkent - gorod khlebnii). In this tale, a young boy sets out on a harrowing journey from his remote village to Tashkent, hoping to find grain for his starving family. Along the way he faces death and despair as well as muzhiks who simply want to toss him out of a moving train. But amid the cruelty the boy also finds friendship and kindness. He eventually returns home to the sad news that most of his family is dead. He is able to look past the tragedy, however, and confidently pledges to build everything anew. During the summer of 1923, Neverov visited the Samara region again. It was during this time that he was working on the novel Geese-Swans (Gusi-lebedi). It is set in a remote village in 1918 where the peasants try to make sense of the revolutionary events, trying to understand the difference between the Bolsheviks and the S-Rs. A.S. Neverov died suddenly on 24 December 1923, the result of an acute asthma attack. |