Presents a summary of:

FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF ETERNITY

by Pavlo Zagrebelny

(1971)

1. A rolling-shop foreman at a Ukrainian pipe factory, Matvei Sergeevich Chereda, had three daughters--Izida, Antonida, and Ziniaida, or "Zizi". Finally, in the year of the victory over the fascists, a son was born--Mitko.

Izida married a cellist, who soon became famous, galavanting off to and winning numerous international competitions. Antonida married a young engineer who went off to invent and mechanize on a kolkhoz.

|

|

A government commission shows up at the factory to investigate Mitko's workshop. The chairman is an old friend of Mitko's father, who is now retired. Mitko is called to testify. Before he can even sit down, the chairman launches into a diatribe against Mitko and the entire younger generation who, he says, are not working responsibly or with enthusiasm. Mitko refuses to anwser any questions, remaining stubbornly silent. This is interpreted as a mutiny and causes Mitko to get tossed out of the office in ignomy.

Oops...the whole affair with the commission never really happened. It was just a story Mitko made up.

2. Mitko liked to make things up. When he was 10 or 11 he made up a disease. He conviced himself, as well as everyone else, that he had the imaginary disease. He would lie on the couch for weeks at a time, getting lazier and lazier. His friend Yenya would visit him and talk about the interesting things out in the world. In the 10th grade, Yenya would brag about his studies. One day, Mitko got tired of this, so he got up out of his death bed and went to sign up at the factory. He now bragged to Yenya that he was a member of the working class, working to bring the future closer. Yenya, ashamed, said if it weren't for his father, he, too, would give up his studies and become a worker.

This "work" was all propaganda, however. In fact, Mitko was a useless worker, shuffling from department to department, undertaking occassional unimportant tasks. He was accomplishing nothing and learning nothing.

When called up for his compulsory military service, Mitko was assigned to the tank corps. Surprisingly, he liked military life. Remembering stories of his school history teacher, Mitko told his fellow soldiers about the ancient Greek city of Sybaris and the Sybarites---how they invented the chamber pot, piped wine into their houses through the tap, and how one died of shock when he saw how hard the peasants had to work. As a result, Mitko himself won the nickname of Sybarite.

Mitko began to pursue the goal sought by all adult humans: prestige. But he forgot that in this area, as is all human pursuits, one cannot advance without preparation. On their very first night maneuver, Mitko decided to take up the position of the tank commander, and stood in the open hatch. As the tank lurched into a ditch, Mitko was catapaulted out of the turrent and crashed to the ground, seriously injuring his back. When he regained consciousness, he was in a little hut in the forest, being tended to by an old woman. He lapsed into and out of sleep, and during one of his surfacings he saw a beautiful girl's grey eyes--like an early dawn on a warm summer's day--looking at him

|

|

Mitko comes home from his tank duty and is surprised to find that Yenya has given up a budding carrer as a diplomat and is now working at the factory, apprenticed to the grumpy, taciturn, and machinelike Chemeris, the best cold-roller in the nation. Mitko also senses that Yenya has a girlfriend and bullies Yenya to introduce him to her. Reluctantly, Yenya takes Mitko to a relatively secluded clearning where a a group of good-looking boys are gathered silently in a circle around a tall, bony girl named Alya. All of the boys are looking upward, neither at Alya nor at the sky. Puzzled by the absurd scene, Mitko breaks the silence, asking if this is some sort of cult. Alya shoots back, "A cult of morons."

|

by the Factory Poet When I fill in the space on a form: "Profession", I state with pride: "Rolling is my game; profession: pipe roller. It's my life, and it's a good one. Let others go through life regretting they are what they are, But I am proud, for our pipes are the arteries of the country's oil, That oil which is given us in copious supply by our brothers, my war-time comrades from Baku. From Baku they send us their tankers forth Upon the sea. Perhaps they do not know me there The sea is no little brook, no quiet backwater, I agree... But they might ask, "Those pipes in the sea-- Who makes them?" The doctor innoculates his patients against disease. The patients would surely like to know: His needles are also from my mill. I look about me with pride To see, on one side, fountains of oil, On another, water flowing into the fields, On another, ships standing on their stocks, in dry dock. See the engineer build a new machine. And urge his crack brigade: "Give us a pipe, lads, a special pipe!" "You'll get your pipe," I reply, "So special you won't believe it! A pipe for the sky, the sea, the dry land, Pipes for all manner of motors and machines!" |

Mitko goes to the factory to see Tokovoi, the deputy shop superintendent. It was Tokovoi who had squeezed Mitko's father out of the factory, to make room for his own team. So, Mitko assumed he wouldn't get too warm of a reception. Tokovoi, however, seems to take an interest in getting Mitko a factory job and asks where he'd like to work. Without really knowing why, Mitko says he wants to work with Shlyakhtich. Tokovoi nods approvingly.

5. Alya signs up for courses at the People's University of Culture. So do all her admireres, including Yenya, who now prefers to be called Yevgen. Mitko feels he can't let Yevgen go off on his own like this, so Mitko enrolls, too. All the instructors also seem to fall under Alya's mysterious sway. The most brazen is Kryzhen, the literature teacher. During breaks, he comes up to Alya to ask if she heard what he said in his lecture. Alya is as disdainful of him as of all her other admirers.

During one lecture, Kryzhen quotes Spinoza, saying that the spirit is eternal , because it embraces all phenomena from the point of view of eternity. Alya's retort is, "From the point of view of eternity, you're a half-wit."

It turns out that Alya is the daughter of Cheremis, to whom Yevgen has been apprenticed. Later, Yevgen is sent out to work on his own, and Tokovoi assigns Mitko as Cheremis's apprentice.

Cheremis is a nationally acclaimed pipe roller, a Hero of Socialist Labor, who could do four times the norm in one shift. He is visited constantly by Komsomolists, leading workers, reporters. Cheremis respectfully endures these visits, but is always be eager to get back to work. He drives Mitko very hard, and Mitko sometimes dreams of chucking it all and walking back to that hut in the tankodrome forest to see those beautiful grey eyes again.

|

|

Mikto and Yevgen were inspirted by Shlyakhtich, but they could never understand his lack of concern for creature comforts and the fact that he seemed totally indifferent to woman, even though he could have had any of the factory beauties he wanted. Mikto and Yevgen could find no explanation for this. But, as Shlyakhtich said, "If everything in the world could be explained, Don Quixote would never have been written." Mitko never read Don Quixote--too thick. He and his contemporaries were extremely grateful to Sergei Bondarchuk who saved them oodles of time with his screen adaptation of War and Peace. In fact, Mitko forsees a time when people no longer read, but only soak in the film versions of literature. Although, he admits, there will be some who will still have to chew over those old texts which do not attract even film producers. (Just like us SovLit.com readers!--Com. Chairman)

Mitko's shop is given the assignment of turning out some unusal pipes, for an unsual facility...something to do with atoms or rockets, but no one really knows. For the job, twenty special and complex mills are bought abroad with pure gold. The workers christen the mills "rock 'n' rollers". However, the workers can not figure out the machines, and for more than six days, they are unable to produce even a single pipe.

Finally, Cheremis, a true People's Artist of Pipe Manufacture, masters the rock 'n' rollers. And, soon, Cheremis he is exceeding the norm set for the new pipes. This sets off a frenzy in the press. Reporters flock in with notebook and cameras, hoping to interview the great worker Cheremis. Cheremis, however, is indifferent to all the accolades, and would rather just get on with his work. So Tokovoi is more than willing to provide the press with loads of bombastic quotes.

But then, disaster struck. Alya, who is Cheremis's daughter and works in quality control, finds tiny defects in his pipes, and rejects every single one of them. Cheremis, honest, accepts the shame. Tokovoi, however, sees to it that while the pipes are rejected, Cheremis and Mitko's time and production numbers are not reduced. He even insists that Cheremis continue churing out pipes as before. Cheremis, however, decides to take apart the rock 'n' roller and study it piece by piece.

6. On the surface, Shlyakhtich seemed quiet and polite, but this was just a reflection of the doubts to which he subjected everything around him, especially himself. Tokovoi, on the other hand, was lumpish and nasty, like a bulldozer. No on liked Tokovoi, but they could see that he was forceful, so they usually went along with him. Mitko hid the animosity he felt for Tokovoi for having squeezed his father out of the factory. Tokovoi was trying to do the same with the current shop superintendent.

Relations between Cheremis and his daughter, Alya, were on peaceful terms, not at all imparied by the fact that Alya was daily, unaided by any knife, cutting her father up with her stickling punctiliousness.

Shlyakhtich requests that Mitko and Yevgen be assigned to work with him in an attempt to master one of the rock 'n' rollers. Tokovoi is against this, wanting, for some reason, to keep Mitko with Cheremis. But the shop superintendent, Fyodor Kuzyoma, just back from the sanitarium, sides with Shlyakhtich.

Tokovoi comes snooping around, wanting to find out what Shlyakhtich is up to. The young engineer readily shares his plan: before inserting the skelp into a mill, they will heat it up to 200 or 300 degrees, making the mill's work easier. Much to everyone's surprise, this wasn't Shlyakhtich's idea. No, he got it from foreman Matvei Chereda, Mitko's father. Workers had used this idea during the Great Patriotic war when making pipes for military machinery.

Mitko is angry, assuming that his father had given this idea to Shlyakhtich only on condition that he take Mitko to work with him. His father, however, denies it, and urges Mitko to keep on working with the wise Shlyakhtich.

7. After various trials, Shlyakhtich, Mitko, and Yevgen start actually turning out pipes. But these too are rejected by Alya. The graphite there were using as lubricant burned into the pipes, causing invisible damage.

Shlyakhtich dashes off to the regional capital and comes back with post-graduate student Grisha Frusin, who undertakes various experiments. Grisha is assigned an assistant from the pipe institute, a friend of Zizi's named Diana. Diana is an exquisite beauty, far beyond the bounds of natural phenomena for the factory. She was so extraordinary that Mitko decides she should marry Shlyakhtich, who is very extraordinary himself. He tells this to Shlyakhtich, who does not even smile. A few days later, Shlyakhtich brings Mitko a large album called The Beauty of Women, containing eight or nine centuries worth of artists' renditions of beautiful women. And not one of the pictures is the same. So, Shlyakhtich points out, beauty is all subjective, like idealism.

While Diana is beautiful, she is a terrible record-keeper, and Grisha demands that she be replaced. So Zizi comes to take over for her.

Mitko's shop of course fails to meet the state plan, so a government commission is to be sent to investigate.

At the Chereda home, Zizi, as usual, is turning things topsy-turvey. She scatters about a folder of clippings that her father is keeping. This provokes a severe reprimand from her mother, who reveals that her father needs the clippings because he is writing his memoirs. This comes as quite a suprise to Mitko and Zizi. Matvei, their father, had never held a gun, never engaged in any adventures. His whole life had been just the factory, like hundreds of millions of others. So what did he have to write about? Sheepishly, Matvei replies that he's writing on "Commitment to communist ideas." Zizi impulsively kisses her father, and she and Mitko gather up the clippings again.

|

|

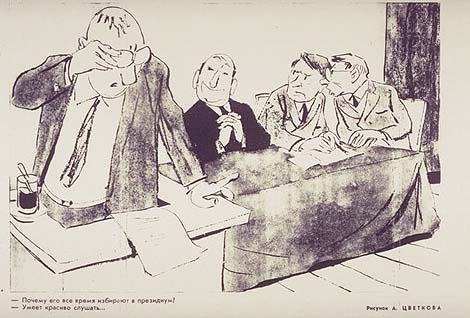

-Why is he always chosen to sit on the presidium? -Because he listens so nicely. From Krokodil, 1965. Artist A. Tsvetkov http://newarkwww.rutgers.edu/pubadmin/russianposters/toon1965.html |

Mitko recalls that his father's whole life was the factory. The home was the domain of his mother. To illustrate, Mitko recounts the incident of the kitchen tap. One evening, the tap in the kitchen began leaking. His mother "bandaged" it up with a cloth, hoping that that would do until a plumber could be called in the morning. However, soon, the tap wasn't working at all--water was flowing freely into the sink, and the drain hole could just barely keep up with it. Panicking, his wife ordered Matvei to do something. Matvei got a wrench and started fiddling around with the tap, until eventually it came off completely, and water gushed out, quickly filling the sink. Matvei and his wife got buckets and kept carrying water to the bathtub. Matvei rushed down to the boiler room to see if he could find a turn-off valve. The boiler room was locked, so he had to brake in with a crowbar. Inside the boiler room, a vicious dog stood guard and wouldn't let Matvei pass. He tried to bribe the dog with a sausage, but the dog just ate the meat and still wouldn't step aside. So Matvei heroically flung himself at the dog, getting bitten badly in the hand in the process. Having defeated the canine, Matvei managed to turn off all the valves he could find, solving the problem. Of course, the boilers almost blew up becase no water was flowing to them, but the porter turned on the proper valves just in time.

9. After a hard day at work, Mitko comes home and is shocked to see Tokovoi there with his parents and Zizi. Tokovoi has brought a transparent plastic ventilator as a present and is installing it in the kitchen. Mitko cannot for the life of him figure out why Tokovoi, the man who put his father out on pension, is here, trying to ingratiate himself. Then Mitko realizes that Tokovoi has taken a liking to Zizi. Mitko angrily whispers to Zizi that she should have made him do something more useful...like jump off the balcony.

Rudely, Mitko demands to know why Tokovoi forced his father into retirement. Tokovoi hems and haws, saying that he just signed the order, that he was just following instructions...general instructions, not specific ones. Zizi then comes rushing into the kitchen screaming that she's dropped something. Seeing his chance to escape Mitko's inquiry, Tokovoi hurries to Zizi and follows her out onto the balcony. She points down to the ground, two stories below, where her gold and ruby earrings are lying. Tokovoi says he'll quickly run downstairs and fetch them. Zizi reacts with disappointment, saying that she had hoped he would have been more direct and leapt off the balcony to get them. Tokovoi is reluctant, but realizing the role he must play as a suitor, he climbs over the balcony railing and jumps off. Zizi and Mitko erupt in laughter.

Later, Mitko tells Zizi that she should be ashamed of involving herself with Tokovoi. She tells Mitko that it's none of his business, and they have a bitter fight about it.

The next day at the factory, Mitko tells Shlyakhtich that Zizi is a spy for Tokovoi's camp. Shlyakhtich shrugs it off, saying they have nothing to hide.

10. Shlyakhtich drives his team hard, keeping them at work long after the normal shift has ended. He urges them to work for a higher purpose, like Lenin. Grisha, who has conducted experiments on over a thousand variations of pipes and temperatures, grows increasingly frustrated, claiming that he's no longer a scientist, just a a hacksaw wielder, who saws pipes into pieces and heats them up. Shlyakhtich counters that Grisha makes experiements and that is where scientific investigation begins. Grisha points out that Mitko and Yevgen are also making experiments, only on whole pipes, not just sections. Skhlyakhtich agrees that perhaps Mitko and Yevgen are greater scientists than both of them. Zizi just smiles mockingly at the whole group, thinking them all mad.

Mitko views Shlyakhtich and Grisha, in their lofty freakishness, somewhat akin to poets, like the factory poet who was on the radio last week reading his dismal "Heaving with blistered and calloused hands, we row toward the distant shore." Mitko feels that, in this case, the poet has it right. In their work with the rock 'n' rollers they have drifted so far from one shore that they will never get back, and they will never land at the other side. But when the poet cries, "But, lo! We shall vanish entirely!", Mitko gets mad, refusing to disappear. Mitko decides that poets should not be allowed to hang out with everyday people, scrutinizing their every step, seeing the end of the world in their least failure. In olden days, poets, like Homer, were blind; unfortunately this custom has fallen out of practice.

Tokovoi enters and announces that Shlyakhtich has been summoned by the government commission and is wanted in the director's officer immediately. Shlyakhtich says that his shift ended hours ago and that he's not here. Mitko and Yevgen take advantage of the opportunity to leave and follow Alya down a corridor.

11. The factory management offices are still furnished in the austere fashion of the 1930s. Dark, heavy furniture and telephones; gigantic inkwells which, of course, no one used anymore. The fierce secretary looks up in alarm as three unwanted visitors--Mitko, Matvei, and Yevgen--enter. They announce that they want to see the director. The secretary says he's meeting with the government commission and has no time for them.

The trio goes outside to wait. Shortly, the chairman of the commission emerges on his way to his car. Matvei speaks up, saying he wants to talk about the cold-rolling mill. The chairman angrily lashes out that they're wrecking an important goverment project, the shop should be closed down, the superintendent expelled from the Party, and brought to trial. He calms down somewhat as he recognizes Matvei as an old acquaintance. Tokovoi rushes up, attempting to save the chairman from Matvei and the others. The chairman, however, shoos Tokovoi away and confers quietly with Matvei.

Oops...the meeting with the chairman never happened. Just another story that Mitko made up. Sorry, never mind.

|

1911-1987  Listen to the: The Comedy of Arkady Raikin |

12. A factory meeting is called. On the presidiuim sits the entire government commission, lead by the chairman, Aleksandr Nikolaevich. Mitko knows the chairman the way he knows the comedian Arkady Raikin: he sees Raikin on television all the time, but Raikin doesn't see him.

The chairman and Mitko's father, Matvei, had grown up together here in the same factory village. They each married a Komsomol girl and worked through the Civil War and post-war era. Then, one bright young steel worker was to be chosen to go to Sweden to study steel making there. Aleksandr, not Matvei, was chosen. He returned two years later, sporting fancy clothes. As a specialist with foreign education, he was appointed chairman of some commissioin and went off on a trip around the country. He never returned. During the Great Patriotic War, the factory was evacuated to the Urals. It was quickly reassembled, but work couldn't begin on time because the main rotor for the blooming mill motor was lost on the railroad somewhere. A government commission, headed by Aleksandr Nikolaevich, arrived to investigate. Aleksandr berated the chief engineer (who today is the factory director). But the engineer calmed Aleksandr by remembering the number of the truck onto which the rotor was loaded. During this trip, Aleksandr paid a visit on Matvei, to talk over old times. Aleksandr let it be known that he moved in high circles these days. He implied, however, that there was also some danger for him in these circles and he wanted to know if he could rely on the workers' support. Matvei assured him that he could. Aleksandr promised to visit and keep in touch, but he did not.

Also on the presidium is the factory Party committee chairman, Vasilenko, a relatively younger man whom the workers know as a fighter for justice, integrity, and honesty. When Mitko and Yevgen were in the 8th grade, Yevgen had quite a crush on Vasilenko's wife, who was their literature teacher.

13. The meeting begins. The first to take the floor after the director is Tokovoi. He says he employes Party methods in organization and instruction and blah, blah, blah. He then quotes some poetry, but the chairman tells him to stick to facts. Tokovoi asserts that they won't be able to meet the state plan. The reason, he claims, is that they've forgotten about the average, hard-working engineer who knows the importance of getting the work done today. They don't need any wonder-workers filled with modernism and abstrationism, working for some abstract future goal. It is clear that the attack is on Shlyakhtich.

The respected head engineer is called up to the rostrum. He asserts that the shop is in disorder and time is slipping away. The chairman scolds him angrily, saying it is the head engineer's responsibility to take charge.

|

|

Tokovoi prevails upon Cheremis, who reluctantly stands up to speak. Referring to Grisha, Cheremis says a man who uses too many words is weak. But, Cheremis admits, contrary to all publicity, Cheremis is rolling rejects, not pipes. And just because they paid gold for those damn rock 'n' rollers doesn't mean they're any good. A pipe roller working on a mill is like an artist playing on the violin or accordion. But in this case, the new accordion they bought for him with solid gold is no damn good. Cheremis says he's a simple man who gives his sweat willingly. What else is there besides sweat? Brains. And Shlyakhtich is racking his brains to make a new accordion. Cheremis says he supports Skhlyakhtich because if he succeeds in making a better accordion, it will be good for everyone.

The chairman commandingly tells Shlyakhtich to come up and speak. Shlyakhtich declines. Vasilenko asks nicely, and Shlyakhtich immediately jumps up to the rostrum. He says that Tokovoi has been glorifying the abilities of mediocre specialists. But, Shlyakhtich goes on, most people support modern ideas. The only ones shouting about sticking to rules and about the value of mediocrity are those you have torn themselves away from the people. For the people have a natural drive toward perfection.

Tokovoi counters that people like Shlyakhtich are never satisfied, they always pit themselves against the collective. He says that Shlyakhtich is an enemy of society, thirsting for private glory. As proof, he sites the fact that Shlyakhtich is working twelve-hour shifts, long after everyone else has gone, leaving his disabled father, Vasil Shlyakhtich, alone at home with no one to take care of him. Tokovoi continues, "The time for zealots is gone! The iron commissars have left us along with the era of war communism."

| |

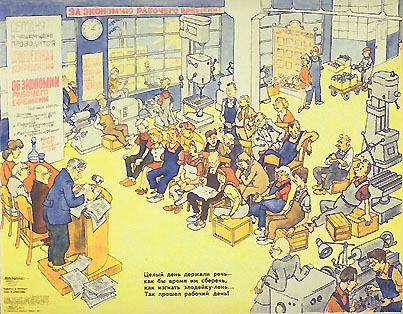

|

They talked and talked all day long About how to save their time, And how to defeat the lazy loafer. And so wasted the whole day. |

Öåëûé äåíü äåðæàëè ðå÷ü êàê áû âðåìÿ èì ñáåðå÷ü êàê èçãíàòü çëîäåéêó-ëåíü Òàê ïðîøåë ðàáî÷èé äåíü! |

|

Artist: V. Kunnap; Poet: V. Alekseyev; 1977 (http://newarkwww.rutgers.edu/pubadmin/russianposters/pencil1977.html) | |

Tokovoi spends so much time talking about work, he's forgotten how to work properly, Shlyakhtich says. Idlers are always suspicious of hard workers. We must try to emulate Lenin's industriousness. And as concerns his father, Shlyakhtich says that's where he got his determination from.

The chairman closes the meeting. It's obvious, he says, that one workshop is too small for two engineers like Tokovoi and Shlyakhtich. But the work must be done. They'll take notice of who comes in first and come down heavily on the one who falls behind.

14.

Vasil Shlyahtich's father was a factory blacksmith. He participated in the events of the Revolution and Civil War and, thus, had little time for his son. The family lived in the Clay Hill section of town. Vasil, when he was 13, fell in with a 16-year-old named Nazarko and a fellow 13-year-old named Baistryuk. They drifted into an anti-social life of petty crime, drinking, etc. As the years passed, they would sometimes go to work at the factory, but never for long. Soon, they would be up to their old tricks again, their crimes getting more brazen. Nazarko and Vasil got married. One day, Baistryuk got into some trouble. To save himself, he ratted on Vasil and Nazarko, who were arrested, tried, and sent off to prison. Vasil was released at the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. Two days after the last Soviet soldier pulled out of the town, Vasil arrived, returning to his wife, Tatyana, and his son, Lyonya, who had been born in his absence.

Soon, the Nazis came and occupied the town. Baistryuk, wearing a vaugely German uniform and carrying a rifle, shows up at Vasil's home. He apologizes for having ratted on Vasil before, saying that he mainly was trying to get even with Nazarko. Seeing Baistryuk's uniform, Vasil gets an idea and says he wants to work for the Gestapo. Tatyana is horrified, but Vasil says he's got a plan. Baistryuk recommends Vasil to the Germans, and he gets a job as a Gestapo sentry.

One day, when Vasil is guarding Gestapo headquarters, a stout man comes up to him and whispers that he's discovered a group of Bolsheviks handing out leaflets and that he knows where their next meeting is to be held. Vasil arranged to meet the man outside the conspirators' building before that meeting.

Vasil then went to Gestapo chief Grunbeck and told him that he had discovered a distributor of leaflets and asked permission to arrest him. The next day, Grunbeck and other Germans accompanied Vasil as he went to the meeting site. When the informer arrived, Vasil walked up to him and immediately shot him in the head. Grunbeck said that it would have been better to take him alive and question him, but in general he applauded Vasil's murderous ruthlessness.

Following this event, Vasil was steadily promoted in the Gestapo ranks, becoming Grunbeck's right-hand man and the terror of the town. In secret, he carried out a single-handed battle against the Nazis. When he obtained lists of intended hostages, he warned them, giving them the chance to escape. When anonymous denunciations were received, he tried to tip off the victims. He dealt cruely with any traitors who tried to expose underground cells or the like to him.

15.

When the day of the town's liberation came, Vasil was ordered to retreat with Grunbeck. Reluctantly, Vasil obeys. But not for long. When a Soviet airplane attacks the German column, Vasil kills Grunbeck, takes the car loaded with German documents, and heads back to town. Along the way, he was arrested by a Soviet lieutenant who assumed he was simply a traitor. A general shows up quickly, however, and Vasil is released. The general is angry at Vasil for disobeying orders and commands him to take the car and rejoin the Germans.

Vasil did as he was told, retreating with the Germans all the way to Berlin. Just before the end of the war Vasil and other Soviet collaborators were gathered under the command of a former tsarist colonel named Uncle Boris and moved to a castle in the Bavarian Alps. After the war, a Mr. Tomaso, an Italian from America, showed up to train the group as spies and saboteurs to be sent back to the Soviet Union.

Vasil exceled in his studies, but always managed to defer being sent back to the USSR himself, having decided that it is best that he learn as much as possible about Tomaso's operation and the missions of the other spies. Vasil got promoted to instructor and only then did he decide that it was time for him to make his escape.

Vasil went into the village with another student, a red-headed fellow named Yukhim. They went drinking at a local inn. Convinced that Yukhim was blind drunk, Vasil walked out of the tavern and sat in the back seat of a Mercedes. He took out a gun and ordered the driver to get going. Yukhim, who was only pretending to be drunk, hopped in the sidecar of a motorcycle and, also pointing a gun, ordered the motorcyclist to chase the Mercedes. The narrow village streets favored the motorcycle, so Yukhim caught up to the Mercedes. He opened fire. Vasil was wounded twice in the leg. He fired back. The motorcycle swerved and crashed.

Established on October 16, 1939, it was conferred over 12,700 times. Learn more at: Orders and Medals of the USSR |

16.

Vasil wanted to work somewhere where he would not stand out from others, so he took a job selling various sundries from a kiosk at the factory gate. He was very good at getting supplies of macaroni in those hungry post-war years and was always willing to sell things on credit, and so he was on good terms with everyone.

Visit the: Klavdiya Shulzhenko Museum-Club Then listen to her and other Soviet singers at: Great Songs from the Soviet Past |

17. After the factory meeting, the government commission got in their cars and drove away, without making any definite statement. Mitko is happy, feeling that Tokovoi has been trounced. Yevgen, however, warns that it might not be over yet.

Back at home, Mitko finds Zizi getting ready to go on a picnic with Tokovoi. He tells her that Tokovoi just suffered a great humilation at the factory and probably won't even show up. Besides, he advises, Zizi should not hook herself up to a falling star. Zizi, of course, ignores Mitko. And Tokovoi does show up, just as smug and happy as ever. in fact, acting like a winner, he advises Mitko to leave Shlyakhktich for more sensible people.

|

Quote the words of Aleksandr Blok:  "So her pointless youth rushed by Wearing itself out in empty dreams And the iron grief of the railway Whistled, tearing her heart to pieces." Here's more: Works of Aleksandr Blok |

Oops...the whole picnic scene was just another one of Mitko's fantasies. Here's what really happened:

A half hour after she left, Zizi returned, saying she's dumped Tokovoi because he's always either sighing or being hearty and she can never tell which is which. Mitko is happy and says she should pay attention to Shlyakhtich. But Zizi just scoffs.

18. Next week, Mitko reports to work and is summoned to Tokovoi's office. Mitko is reassigned to work for Cheremis, and Shlyakhtich is to be transferred as well. Mitko protests, saying that, from the point of view of eternity there are some behests--Lenin's behests to strengthen, protect, and improve the friendships of peoples, the Soviet Union, the army the Party; and to study. So far in his life, all these things have been done without Mitko's participation. Now he also wants to fulfill Lenin's behests to the best of his ability. And it is Shlyakhtich who is giving him the opportunity to do something to improve humanity. Like his brother-in-law the cellist says, "Each new note enriches the world."

Shlyakhtich, looking haggard, enters and tells Mitko that he and Grisha have come up with something new and they must get to work immediately. Tokovoi orders Shlyakhtich to cease all experiments. Shlyakhtich ignores Tokovoi and goes to his work station, with Mitko obediantly following.

19. Shlyakhtich tells Mitko that he and Grisha have discovered that they should heat the skelps to 120-160 degrees, not to the 300-600 degress they were trying before. The higher temperatures cause deformation in the metal.

Yevgen doesn't show up for work. Mitko keeps asking, but Shlyakhtich aways ignores the question.

They work all day at 160 degrees, without success. Shlyakhtich says tomorrow they will work at 120 degrees and undoubtly have success. Mitko again asks about Yevgen and Shlyakhtich only enigmatically says that something has happened with him.

Mitko hurries to Yevgen's apartment and is surprised to see Grisha already there. Yevgen is lying morosely on the sofa, refusing to move or say anything. Grisha then gives Mitko the shocking news: Alya is with Shlyakhtich.

20. Grisha departs, leaving Mitko alone with the grieving Yevgen. They sit in stunned silence for some time. Then a surprise visitor arrives--Shlyakhtich's father, Vasil. He brings a bottle and some glasses. Yevgen reluctantly drinks as Vasil tries to console him, saying that they are both bachelors again.

Vasil says that Alya just showed up at their apartment a few days ago, telling Shlyakhtich that she wanted to be with him now because she knows he's going through a difficult time. What else they said Vasil doesn't know, because they sat off alone, acting as if Vasil didn't exist. At this very moment Alya is at their apartment, but Shlyakhtich isn't--he's off at the factory or his lab.

Mitko goes home where his father gives him some more stunning news: Zizi has run off, abandoning work and everything. She's gone off on her own, and no one knows where she is. The reason for this, Matvei says, is that she just couldn't get Shlyakhtich out of her heart, which, apparently was obvious to everyone in the family except Mitko. All her boyfriends, even the sham romance with Tokovoi, were all part of her plan to get Shlyakhtich.

21. Confused, Mitko runs out of the apartment, thinking that he's going back to Yevgen's. Instead he decides to go to Shlyakhtich's and somehow exact vengeance for what they've done to Yevgen. When he gets there, Alya is home alone. She is not particularly surprised to see Mitko. She seems quiet and relaxed, not the vengeanful vixen of before. She invites Mitko in and tells him that Shlyakhtich has telephoned and will be home soon. Mitko opens his mouth, intending to deliver some insult or blistering tirade, but instead he mumbles words of congratulation to Alya and Shlyakhtich, then runs off.

Mitko goes back to Yevgen's. Vasil is still there, and he has been joined by Mitko's father, Matvei. Vasil is sitting on the sofa with Yevgen, crying. It looks as if Yevgen is consoling Vasil.

Zizi, back in the regional capital, sends a telegram asking her mother to forward a blouse which she forgot.

|

|

Shlyakhtich and Alya invite the others to their place for a little celebration. Yevgen says he has a headache, so Alya suggests that he walk around for a bit and come later when he feels better. Mitko accompanies Yevgen as he purposefully walks to Clay Hill, which is now called Cosmonaut Square, with a wide avenue, Gagarin Prospect cutting across it. Mitko says he understands how Yevgen feels, and tells Yevgen about the grey eyes he saw when thrown out of a tank and about how they still haunt his dreams. They decide to go to the Shlyakhktiches'.

22. Mitko and Yevgen arrive at the Shlyakhtiches' where a regular party is in progress. Besides Shlyakhtich and Alya, also present are Vasil, Cheremis, Matvei, Mitko's mother, Yevgen's aunt, Vasilenko, the factory director, the factory poet, and Tokovoi.

The factory poet says he's just submitted an essay entitled "Science Forcasting the Future" to the newspaper, but now, Shlyakhtich's success has changed everything, so he has to withdraw the essay.

Mitko whispers to Shlyakhtich, asking if he's going to have it out with Tokovoi. Shlyakhtich and Vasilenko exchange a glance indicating that it's not worth getting into today and, besides, Tokovoi will eventually get what's coming to him.

Mitko tries to provoke Tokovoi, but Tokovoi says he was only testing Mitko, to see if he could be easily scared. Vasilenko notes, "Whoever tries to pit force against reason ends up looking ridiculous." And Mitko adds, "From the point of view of eternity."

After a few glasses of vodka, Yevgen picks on the poet, saying that poems should be written about beauty, not pipes. The poet responds:

Our pipes are necessary to hundreds of machines and dozens of factories--to the entire national economy. Before a new pipe is created, thousands of people have already dreamed about it, know what it should be like, what quality it should be. They even know how it should be made. They know, but they can't actually make it, only one person can--or a group of people. They close the chain of creating, forming its final link. In a way they are related to writers, for a writer is both a beginning and an end in one person. And these skilled craftsmen, creators of new products, close a process begun by someone else, but they close it in a creative way, with inspiration. And if I sat next to human creation, why should I not sing its praises? |

23. Mitko and Yevgen continue their work happily, filled with a sense of their own worth, engendered by the traditions of their fathers and grandfathers. A man who does not draw on the heritage of his ancestors is empty; where else can he get his dignity as a worker?

The entire shop shifts over to Shlyakhtich's method. Tokovoi putters around, making himself the organizer, trying to make it seem that nothing would have been achieved without him. When guests and scientists come to study the new method, it is Tokovoi who takes them around.

Established in 1925 for outstanding achievements in various fields of science, technology, literature, art, and architecture. It was not awarded between 1935 and 1957, having temporarily been eclipsed by the Stalin Prize. |

One day, Tokovoi pulls Shlyakhktich aside and says it's time to apply for the Lenin Prize. Shlyakhtich refuses the suggestion. The distinction would be too great, and besides, it's unseemly and ridiculously bureaucratic to "apply" for a prize. This doesn't stop Tokovoi, who gets the paperwork underway. Soon, the newspaper announces a Lenin Prize nomination "For the elaboration and application of a fundamentally new pipe-rolling technique." And who are the names attached to the application? First of all, the director of the factory, followed by the director of Grisha's scientific institute, the factory chief engineer, and Tokovoi. Only then, at the bottom of the list, do we see the names of Shlyakhtich, Grisha, Yevgen, and Mitko.

Shlyakhtich thinks that the Lenin Prize is the highest award a man can dream up. At the same time, it is a reward for the past, and it is necessary to prove that you are essential to people today, tomorrow, everyday. So perhaps that's why prizes only do young people harm, Shlyakhtich thinks.

A film crew shows up to film the nominees. Tokovoi, of course, pushes himself front and center. The director tries to set up a scene with Mitko and Yevgen working in the background while Shlyakhtich engages in unnatural conversation with the foreman in the foreground. Shlyakhtich refuses to participate in this phony carnival antic and walks off, as do Mitko and Yevgen. Tokovoi is more than happy to fill in, spouting all sorts of nonsense and engaging in ponderous discussions with the chief engineer for the camera.

Because of Tokovoi's budding cinematic career, no work is getting done in the shop. On the second day of filming, the factory director and Vasilenko turn up to observe. Seeing Tokovoi's antics, Vasilenko immediately stops the filming, calling it nothing but useless discussion. The director protests, saying that he needs commentary. Vasilenko says that the workers will return to their mills and start rolling pipes--"work and action, that is the mettalurgist's commentary."

While walking home from work, Yevgen and Mitko meet two pretty young girls, one dressed in pink, one in blue. They engage in some playful banter, then, before departing, the girls tell Mitko and Yevgen to meet them tomorrow evening at the pedagogical institute.

Aleksandr Nikolaevich, the commission chairman, returns to town...this time, without a commission. He meets with the factory director, Vasilenko, Vasil and Matvei to ask how the undeserving could possibly get listed on the nomination. The factory director says he relied on information from Tokovoi.

Vasil and Matvei suggest that their sons' names be removed from the lists. They recall that during the Great Patriotic War some people received medals that they didn't deserve, and, afterwards, they just lived off the glory of these medals, accomplishing nothing useful. Unfortunately, the same is true of some who actually earned their medals. Aleksandr Nikolaevich doesn't like this idea. Nor does he like Tokovoi, who is a situational person, one who takes advantage of situations that arise. He's got a diploma, senority, a big mouth...every thing except talent.

A few months later, the Lenin Prize winners are announced. The only winners are Shlyakhtich, Grisha, Yevgen, and Mitko. But long before that, Yevgen and Mitko hurry to the pedagogical institute on Cosmonaut Square, to keep their date with the blue and pink girls. Many people pour out of the building at closing time, but not the blue and pink girls. It's obvious that Yeven and Mitko have been stood up. Mitko thinks:

|

On that very spot, in rain-drenched Cosmonaut Square, the thought came to me that I wanted to live every day like a holiday, surrounded by joyous bird-song, but the green rustle of leaves, and by the calm glow of the grey eyes. And by iron? By our own beloved iron, which had become the very essence of existence for Yevgen and me? Yes, by that too. By iron, too. From the point of view of eternity. |

|

Zagrebelny, Pavlo Arkhipovich. Ukrainian writer born on 25 August 1924 in the village of Soloshino in the Poltava Region. After finishing school at age 17, he enlisted in the army and fought in the defense of Kiev and in the battle on the approaches to Bryansk. He was wounded several times. In 1945, Zagrebelny worked in the Soviet military mission in West Germany. Later, he pursued a degree in philology at Dnepropetrovsk University. His works include Thoughts on Immortality (1957), Heat (1961), The Miracle (1968) and From the Point of View of Eternity (1971). In 1974 he won the Ukrainian Shevchenko Prize, and in 1980 he was awarded the USSR State Prize. He has also authored a series of historical novels about the Kievian Rus including Divo and Evpraksiya. Other titles include Roxsolana, Ya, Bogdan, Smert u Kievi, Pervomist, Pivdenii Komfort, and Yulia. |