Presents a summary of:

THE FOUNDATION PIT

by

Andrei Platonov

(1930)

Presents a summary of:

THE FOUNDATION PIT

by

Andrei Platonov

(1930)

). As the activist sees it, "We can't do without the hard sign--it makes a slogan tough and precise. It's the soft sign that should be abolished."In a dusty little town, a worker named Voshchev is fired from his job at a small machine factory. The management says he just stands around thinking while everyone else is working. Voshchev tries to defend himself, saying that he is trying to work out a plan for life, a way of achieving happiness and spiritual meaning which would raise productivity. The trade union committee is unimpressed, saying that "Happiness will come from materialism, not from meaning." Further, they ask, "What if we all suddenly get carried away thinking--who will be left to act?"

My body gets weak without truth.

Voshchev protests, saying, "If they don't think, people act senselessly!"

Having nowhere to go, Voshchev sets off wandering down the road. He comes upon an isolated road keeper's house. The roadkeeper and his wife are loudly arguing in front of their young child, who takes it all in silently. Voshchev rebukes the couple for forgetting what's essential and for not respecting their child, who, after all, will be around long after they are gone. The roadkeeper rudely tells Voshchev to continue on his way. Voshchev resolves to work out the secret of life and return someday to relate it to the child.

Voshchev continues down the road. He feels his body going weak without the truth. He needs to know the exact structure of the entire world and what it is he should aim for.

Voshchev reaches another town. He witnesses a cripple who has lost both legs harass a blacksmith into giving him some tobacco. The cripple is named Zhachev.

Pioneer Days!

The History, Symbols,

and Songs of the

Young Pioneers

of the USSR!

A column of young Pioneer girls goes marching by. Voshchev watches them with a feeling of shame, thinking that they probably know and feel more than he does. Zhachev also watches the girls. Thinking that Zhachev might intend harm to the girls, Voshchev tells him to move off. Zhachev snarls at Voshchev with brutal scorn. It's obvious to Zhachev that Voshchev never fought in a war, and he notes, "A man who's never seen war is like a woman who's never given birth--soft in the head!"

Feeling isolated, Voshchev finds a grassy field and lies down to sleep in it. Around midnight, he is awakened by a man with a scythe, who is mowing down the thick grass. The man tells Voshchev that this empty space has now become a building site and stone buildings will soon be erected.

On the advice of the man with the scythe, Voshchev finds a workers barracks, full of exhausted, sleeping men. Voshchev lies down among them to sleep.

In the morning, the workers size up Voshchev's unimpressive physique. They are uninterested when he says, "My body gets weak without truth."

After breakfast, a trade union representative arrives to give the men a tour of the town, so they can see the significance of the work they are to undertake. They will be building the All-Proletarian Home, a single edifice large enough to house the whole of the local proletariat. The representative has brought a brass band for the occasion. Comrade Safronov, the most politically active of the workers, however, angrily tells the trade union representative that they don't need a band or a tour to raise their consciousness. They know about the squalor on their own. He calls the representative a toady.

The men go out to the new-mown field and begin to dig a foundation pit, which had been marked out by an engineer, to whose resourceful, attentive mind the world had always yielded; and if matter always yielded to precision and perseverance, this meant that it must be barren and dead.

Voshchev works at a much slower pace than the most of the men. Only one weak and emaciated man, Kozlov, works at a slower pace. The other men taunt Kozlov because he masturbates under the covers at night.

After six hours of labor, the engineer says that because it is Saturday, it is time to stop. Safronov on the others, however, saying they have enough energy and enthusiasm, insist on working more.

That night, while the workers are sleeping, Prushevsky, the work supervisor for the All-Proletarian Home, comes to examine the foundation pit. In a year's time, the entire local proletariat will leave the old town and take up residence in the monumental new home. Despite his knowledge, Prushevsky feels that something is preventing him from understanding anything further about life, about the soul. There is no one who really needs him. He is useful to people, but doesn't make anyone happy. In place of hope, all he has now is endurance. So he decides to kill himself. But first he has to write a letter to his sister.

The next morning, digging continues. Pashkin, the chairman of the Regional Trades Union Council, shows up and reprimands the men for working too slowly. Prushevsky arrives up with some more workers. They're all basically unfit--drifters or reeducated former bureaucrats--but there is a shortage of proletarians, so they're set to work.

One of the workers, Chiklin sees that nearby there is a gully which is pretty much the right size for them to use as the foundation pit. He makes this suggestion. After all, it would save them some work. Safronov wants to know where Chiklin gets off thinking up things the educated people haven't thought of. All Chiklin can say in defense is, "When you've nothing to live for, you get to thinking inside your head." Prushevsky, who is basically indifferent to things now that he expects to die soon, orders the men to take some soil samples from the gully.

Voshchev brings soil samples to Prushevsky. He asks the engineer if he knows what nature's all about, how the world was constructed. Prushevsky says he was taught only about the dead bits of this and that, never about the inside of anything or about things as a whole.

Free both of hope and of any desire for satisfaction, Prushevsky spends longer than usual examining the soil samples. "All he wanted was to busy himself with objects and structures, so that they, rather than friendship and personal attachments, would fill his mind and his empty heart."

Zhachev hobbles over to Pashkin's house to collect his regular ration. He crudely abuses Pashkin and Pashkin's wife the whole time. Pashkin's wife is irritated but doesn't say anything, remembering that Zhachev once denounced Pashkin to the Regional Party Committee. Pashkin was cleared, but the investigation dragged on for months, and a big to-do was made over Pashkin's name and patronymic--"Leon Ilych" ("Just whose side is he on?" some asked.)

At the time of the Revolution, dogs howled day and night all over Russia

Zhachev goes off to the workers' barracks and eats some kasha with the men, mainly to demonstrate his equality with the others.

Safronov looks at the bleak landscape and wonders, "why do the fields all look so dreary? Does the world have nothing inside but sorrow?"

Voshchev complains that all they do is dig and sleep. He thinks he would be better off begging around the collective farms. He says, "Without truth I feel ashamed to be alive."

Safronov tries to sympathize with Voshchev, but, he ponders, "Was it not the case that the truth was simply a class enemy? Nowadays, after all, the class enemy was quite capable of sidling its way into your imagination and even your dreams."

Prushevsky, frightened and sad at home, comes to the barracks and sleeps with the workers.

In the morning, Kozlov is shocked to see that Prushevsky--a man from the leadership--is sleeping with the common workers. Kozlov sees this as a violation of the social order and threatens to complain.

Dutch Tiles

The History of Dutch Tiles

and How to Make Them

In talking with Chiklin, Prushevsky recalls a girl he saw many years ago in the pre-Revolutionary days. He can't recall what she looked like, but remembers taking a liking to her as she passed him by, never stopping. Prushevsky wishes he could see this girl again. Chiklin says the girl was probably the daughter of the Dutch-tile factory boss. Chiklin had had his own run-in with this girl when he was working at the factory. One day, she came up to him and kissed him. Thinking her brazen, Chiklin did not respond and just kept walking past her. Prushevsky and Chiklin suppose that by now this girl has grown old and blotchy.

Kozlov decides to go to the Social Security office to get himself an invalid's pension. That way, he will have more free time to keep an eye on everything so as to keep society safe from harm and make sure there aren't any petty-bourgeois uprisings. Safronov brands Kozlov a "parasite...an unprincipled opportunist bent on abandoning the working masses." Kozlov shoots back that Safronov is a wrecker who tried to undermine collectivization by once inciting a poor peasant to slaughter and eat a cock. Safronov ignores this and walks away. "He didn't much like it when people denounced him."

Work on the foundation pit continues. Worn out by the heavy labor, Voshchev is more resigned to his situation. "He contented himself with going out on his days off and collecting all kinds of unfortunate little scraps of nature as documentary proof that the world had been created without a plan, as evidence of the melancholia in every living breath." He tells Safronov that he wants truth so as to increase the productivity of labor. Safronov admonishes him that what the proletariat really lives for is enthusiasm for labor. Chiklin goes to the old Dutch-tile factory, which is abandoned and falling apart. In a remote part of the factory he finds the boss's daughter, who had kissed him so many years ago. She is now a toothless old hag on the brink of death. She is being tended to by her young daughter, named Nastya. The woman (Julia) tells Nastya never to reveal her bourgeois origins. Nastya falls asleep. Chiklin creeps up and kisses Julia, who dies.

Chiklin brings Nastya to live in the barracks. He then brings Prushevsky to the Dutch-tile factory and shows him the dead Julia. Prushevsky is unmoved. In fact, he doesn't even recognize the woman as the young girl he saw long ago. But, he notes, "I never recognized people I loved once I'd got intimate with them--I just yearned for them from a distance."

Chiklin respectfully covers the doorway to the old woman's room with bricks and chunks of rock. "The dead are people, too", he says.

That evening, the men turn their attention to Nastya who is now in their midst. Zhachev secretly decides that once the girl and other children are grown up a bit, he will kill all the local adults--most of whom are egoists and future bloodsuckers.

Safronov questions Nastya about her parents. But Nastya, remembering her mother's warning, says only that when there were bourgeoisie she wasn't born because she didn't want to be; but as soon as Lenin came along, she was happy to be born. Safronov happily concludes, "If kids can forget their own mothers but still have a sense of comrade Lenin, then Soviet power really is here to stay!"

Nastya falls asleep. All the men decide to start working a hour earlier tomorrow on the foundation pit, so that the new home will sooner become a reality and "underage personnel" such as Nastya can be protected. Zhachev approves of the idea, telling the workers, "You're going to wind up stiffs whatever you do...so why not love something small and living and flog yourself to death with labor? Do something decent for once!"

While digging in the gully, the workers unearth 100 empty coffins. Chiklin gives two to Nastya--one for a bed and the other to keep her toys and whatnot in. The next day, a peasant named Yelisey shows up demanding that the coffins be returned to his village. They were all properly measured and premade for the people in his village, including the children. "It's our coffins that keep us alive--they're all we've got left", he says.

It's our coffins that keep us alive--they're all we've got left.

The 98 remaining coffins are tied together in one long line and Yelisey hauls them off by himself. Some time later, Voshchev sets off down the road, following the trail left by the coffins.

Kozlov shows up at the construction site, wearing a three-piece suit and arriving in a car driven by Pashkin. Since leaving the barracks and getting his grade-one pension, Kozlov has become a known and respected active force in society. Each morning, he memorizes little formulae, slogans, lines of poetry, quotes from official documents, etc. Then he goes out and about, uttering these phases in public places and thereby inciting respect and terror. Enigmatically criticizing a food cooperative, he suddenly found himself appointed Chairman of the cooperative's Trade Union Council.

Comrade, Come Join Us

on the Kolkhoz!

Collectivization:

What Happened,

the Impact, and

the Ukrainian Famine

At the foundation pit, Pashkin informs the workers that the peasants in the nearby village are longing for a collective farm. It is decided to send Safronov and Kozlov to the village to keep the blaze of class struggle burning hot.

The foundation pit is complete. All that remains is to fill it in with rubble. Pashkin, however, decides that it's not big enough, since socialist women will soon be brimming with freshness and the entire surface of the earth will soon be swarming with infant persons. The town boss authorizes making the pit four times bigger. On his own initiative, Pashkin decides to make it six times bigger.

Voshchev and a sub-kulak return from the village with the news that Safronov and Kozlov died in a hut. They take Nastya's two coffins to bury them in. Nastya is angry and doesn't understand why the dead get to have the coffins. Chiklin explains, "Once people die, they get to be special."

Chiklin and Voshchev take the coffins to the village, where everything is steeped in the decrepitude of poverty. In the village, the local activist (a bungling and incompetent but nonetheless enthusiastic organizer) tells Chiklin to go to the village Soviet and stand guard over Kozlov and Safronov's corpses, to prevent them from being defiled by a kulak.

When he gets to the village soviet, Chiklin sees that his comrades died of ghastly wounds.

In the morning, the Yelisey and a yellow-eyed peasant come to wash the bodies. Chiklin asks who killed his comrades. The peasants say they don't know. Not satisfied with this answer, Chiklin punches the yellow-eyed peasant. The peasant willingly takes the beating, hoping to receive some serious injury and so win entitlement to a poor peasant's right to life.

Chiklin winds up killing the peasant.

Another peasant mysteriously turns up dead. The village activist identifies the new corpse as the peasant element responsible for the deadly wrecking of Kozlov and Safronov. The activist is confident he would have unmasked this peasant in about thirty minutes anyway.

The activist is glad that there are two dead peasants, saying, "The Center would never have believed me if I said there was one murderer. But two's another matter altogether--that's an entire kulak class and organization."

After the dead are buried, Chiklin receives a letter from Prushevsky. He informs Chiklin that Nastya has started attending nursery school. Nastya herself traced out this message:

LIQUIDATE THE KULAKS AS A CLASS.

LONG LIVE LENIN, KOZLOV AND SAFRONOV

GREETINGS TO THE COLLECTIVE FARM,

BUT NOT THE KULAKS.

The next morning, the activist gathers together the fifty or so rag-tag members of the collective farm. He plans to march them, in star formation, through neighboring villages, where people are still clinging to their private holdings. The weather is dank and windy, and the activist grumbles, "So much for the organization of nature."

The activist had received no directives the previous evening, so he is terrified both of overlooking something and of being overzealous. He had so far collectivized only the village horses, although he agonized over the solitary cows, sheep, etc., since in the hands of a rampant kulak, even a goat could be a level of capitalism.

After the collective farmers set off on their parade, the collectivized horses--on their own initiative and with no human involvement--set off to a ravine to drink and wash themselves. Then they march back into the village and gather up mouthfuls of food. Together they march back into the collective farm yard, drop all the food into a common pile, and only then begin to eat.

Voshchev and Chiklin enter a hut and find a feeble old man lying motionless on a bench. He claims that his soul has left him ever since his horse was collectivized.

In a second hut they find a man lying in a coffin. For several weeks now he has been trying to die, and now, in front of Voshchev and Chiklin, he finally succeeds, and his body goes cold.

Counterrevolutionary Letter!

The Death of the Hard Sign

and Other Adventures in

Russian Orthographics

Later, Voshchev and Chiklin attend a literacy lesson for women and girls, taught by the activist. Strangely, he has the women write all "good", socialist words with a hard sign (tvordii znak) at the end (in violation of the orthographic reform promulgated by the Bolsheviks--ed.

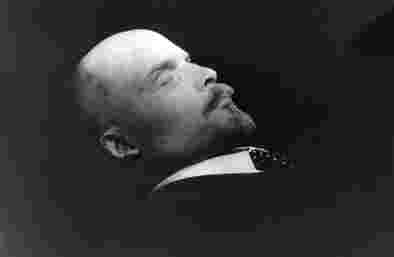

The Lenin Masoleum - Photos, Documents, Articles and a Virtual Tour of the Masoleum |