presents:

presents:

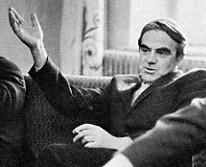

Daniil Granin on The Difference Between Soviet Literature and Western Literature

Let's try to figure out what the fundamental difference is between Soviet writers and writers in the West. I don't know about the theatre or film, but in literature there are any number of serious and interesting prose writers, poets and playwrights in the West.

People read a lot there too. Many interesting books are published. So the main difference between our literary life and that of the West obviously does not lie there.

Then, perhaps, it is in the relations between the writer and the publisher? I don't think so. Not everything is idyllic in my literary work either. I also get involved in all kinds of conflicts and arguments with publishing houses, editors and critics. Most disappointing things sometimes occur. No, the main difference is apparently not there either. Well, then where is it?

When I go abroad I sometimes ask myself whether I could live, say, somewhere in the West as a writer. And the answer is no Why? I will not discuss the many interrelated issues, but will dwell on the purely professional aspects. When I'm abroad and talk to Western writers, I always come up against a strange circumstance: They don't understand us, we don't understand them. They don't understand the nature and character of our literature, the role the writer plays in Soviet society. They don't understand that the aims determining the creative effort of Soviet writers differ from those of Western writers.

Many Western writers call themselves writers in a conflicting society, and progressive men of letters in the West are to a greater or lesser extent in opposition to society, the government and the way of life. They criticize that society, convict it, expose its evils and point out its contradictions. And that is the natural content and meaning of their literary work. That is how they conceive their work. But probably for the first time in the history of mankind, in the history of art, culture and literature, we Soviet writers take an absolutely different position. We defend our society and the principles on which it is based. We affirm it. That is the very positive element which, in the final analysis, is the meaning of our literary activity. And the task of affirming that society is the content of our literature. In that lies the fundamental difference between Soviet literature and the literature of the West. This, it seems to me, is what creates such difficulties in understanding between Western and Soviet men of letters. The traditions of exposure and criticism, after all, number hundreds of years, whereas the traditions of affirming and defending socialist society came into being only with our literature, which had no previous equivalent in human culture.

We criticize much in our society, expose much in our life, diagnosing, so to say, its growing pains. But if one examines the best our men of letters have created, writers of most diverse trends, diverse talents and absolutely diverse creative styles and manners, we see that their literary program was always positive. It was always in defense of those principles on which the development of our democratic socialist society was based. And in the final analysis it was the enthusiasm of affirmation, despite the critical trend of the work. We cannot conceive of literary work without such a positive and constructive program.

I'm an engineer by profession, and later devoted myself to scientific studies. I defended a thesis and was granted a degree. I was very much involved in scientific work, yet I gave up science for literature. Why? Because literature gave me greater opportunities for self-expression. And even more important, it gave me an opportunity to devote myself to what, perhaps, comprises the meaning of my whole life—the defense, advocacy and dissemination of certain philosophical principles, of my concept of life, my civic feelings, principles and feelings I have and which every person defends and advocates to some extent. The affirmation and defense of positive ideals in literature, in art, is certainly very complicated and very difficult because appropriate experience has not yet been amassed, there are no traditions yet. . . . And also because it's always easier to expose and criticize than to affirm. In this sense, it seems to me, the progressive positive program the artist defends is in its historical eventuality always on our side. And the more truthful an artist is, the more resolutely he champions and advocates historic truth, the more significant is his creative work and the higher will the people's appraisal be.

I frequently talk to Western writers. There are many talented artists among them, people whose lives were hard, who had to overcome many difficulties on the road to recognition. But the scantiness of their problems, if one may so put it, sometimes amazes me. The principles they defend or affirm are exceedingly limited, by our measure, anyway. Arthur Miller is a fine master, a splendid psychologist, an outstanding writer, but when I read his works I feel—how shall I put it—the superiority of our society, our history, our life principles, those principles which establish, create, mold a new kind of human. And that is, perhaps, the very reason a Soviet artist, a Soviet writer, a true patriot of his country, could not, would not want to exchange the opportunity of affirming and defending his own society for the Western writer's opportunity of criticizing and exposing his. Despite the great difficulty of our task.

|

|