Presents a summary of:

|

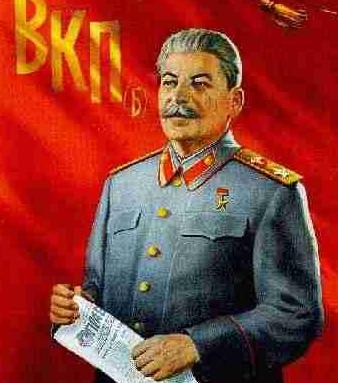

HAPPINESS Stalin Prize Winning Novel by Pyotr Pavlenko ( 1947 ) |

Crimea in Photos then take a: Virtural Tour of Crimea |

CHAPTER ONE

It is December 1944, and the Great Patriotic War is still going on. A boat arrives in a Crimean port, bringing mainly Cossack settlers from the Kuban, complete with livestock and ficus trees. The pier and esplanade--where before the war noisy, merry crowds gathered--are mutilated, bombed out. In fact, the whole town is barren, dead.

On board the boat is also 43-year-old Colonel Aleksei Veniaminovich Voropaev, a war veteran four times wounded, with pulmonary tuberculosis and one prosthetic leg. He is on extended leave and has decided, against all common sense, to come to this town, find a cottage for himself, and live somehow.

The head of the district Party committee, Korytov is suspicious, then merely annoyed, when Voropaev shows up with his documents. Korytov expects all sorts of problems with this absurd colonel. Voropaev admits that he probably made a mistake by coming, but now that he's here he'll try to stay out of Korytov's hair. Kortyov shows Voropaev a map of various houses that are available. They're all in bad shape, and Korytov will not be able to give Voropaev any help with repairs.

Korytov then talks at some length about a topic more to his liking--the massive problems of reconstruction in this ravaged and depopulated district.

It is midnight when Korytov leaves Party headquarters. He decides to go spend the night a nearby kolkhoz. A Party worker named Lena walks along with Voropaev to show him the way. Asking questions, Lena learns that Voropaev is a widower with a seven-year-old son who is ailing. It is for the sake of his son that Voropaev has taken this trip south. Lena hasn't heard from her husband for over three years. He's either dead or has abandoned her.

Voropaev says he doesn't like Korytov, but Lena defends him. She also bewails the desperate situation. They get bread only every third day and no sugar or fats at all. Lena suspects they're not telling the truth to Stalin, otherwise things wouldn't be so bad. Lena disapprovingly thinks Voropaev plans to get a cottage with a few apple trees and become an independent fruit dealer.

At the kolkhoz, crowds of newly arrived settlers are everywhere, milling about, sitting on bundles. There is no order, no discipline. The chairman of the kolkhoz is there. He is Mikola Stoika, a tall handsome man in an army tunic with a Red Star and Sebastopol medal on his chest. He is also missing his left arm. He calls out names of the settlers and assigns them homes. As he does so, he wishes the newcomers happiness in their new life.

|

|

Voropaev spends the night sleeping by a campfire on the kolkhoz. In the morning he awakes and sees Korytov addressing the settlers about the problems and prospects for the new life here. Korytov notices Voropaev and, with some irritation, suggests that he take a job as accountant on the kolkhoz; he'll get a room immediately and maybe someday a house. Voropaev says he'll think about it, then asks if Korytov has heard the latest news from the front. Korytov ignores the question and keeps droning on with his speech.

Voropaev wanders up a hill. From there he can see the whole town and the kolkhoz below. The fragrant scents of grasses and trees waft gently to him. He finds the burned-out shell of a small, four-room house with a kitchen, complete with apple trees and vineyards. Just what Voropaev needs. He imagines fixing it up and from here, with his son, Seryozha, going fishing and to the beach. But then Voropaev realizes that the house is too far away from sources of food and fuel and the school. And how could a one-legged man manage the work and repairs?

|

Splendid Bolshevik  Sergei Kirov Then solve the mystery: Who Killed Kirov? |

Vorapaev, a Siberian native, had long dreamed of living by the sea. He first saw the sea during the Civil War in Astrakhan, when that splendid Bolshevik Sergei Mironovich Kirov, was leading the defense of the city. It was there that Voropaev, serving in the Red Army, had suffered a severe bout with typhus. Later, he was guarding the frontier on the Amur and helped build the city of Komsomolsk. He saw action in north Finland, also. Through it all, only the sea fostered in his mind pictures of repose and complete happiness. At last he was beside the sea, but he might just as well have not come here. He was stranded on the beach like a wrecked ship.

Voropaev comes to see Korytov and right away they begin disputing. Korytov says he likes to generalize. Voropaev says it does no good to generalize and ignore the individual--to honor Stakhanovitism, but to ignore Stakhanov. "There is not a whiff of Marxism in that," he says.

Changing the subject, Korytov asks the purpose of Voropaev's visit. Voropaev says he wants to sign on as a propagandist, only on the condition that he gets an apartment. Korytov agrees, but says that the apartment isn't ready yet so he'll have to settle for a room at present.

Voropaev's first assignment will be to visit and lecture at three kolkhozes, to enthuse the people and build up a Cherkassova movement. Voropaev says Korytov doesn't know what he's talking about. He questions why Korytov is always "bragging" about the difficulties, as if predicting inevitable failure. And why hasn't Korytov enthused the people already? Instead, the people are imbued with doubt and depressed by the difficulties. The argument continues loud and long until they both come to the same conclusion, each thinking he was the first to say: Heroism is organized; it is not elemental. To their bewilderment they see that they weren't arguing, but coming to an agreement.

Voropaev spends the night in Lena's house. Sofia Ivanovna tells Voropaev that he should insist on being assigned a house--even this very house. She points out its advantages (it has about a dozen cherry and apricot trees) and how easily repairs can be made. The old woman says she'll do the washing and watch after Voropaev's son. Voropaev realizes that he wasn't really looking for a house so much as some people with whom he can tie his fate. He says he'll apply for the house and they can split it--2 rooms for Voropaev and 2 rooms for Lena's family.

Voropaev sets off on his lecture tour, hitching a ride in a truck. He begins to feel the way he did before going into battle. He heard recently that his old unit was old unit was crossing the Danube. He imagines all his old comrades in battle. He also recalls the front-line surgeon Aleksandra Ivanovna Goreva. He remembers their first meeting, in the Ukraine in spring time. He was returning to his unit after recovering from this third wound. A bomb exploded nearby and a building wall collapsed to reveal Goreva, crouching over a wounded man on whom she was operating, to protect him from the debris. As soon as she finished the operation, Voropaev moved in and organized the evacuation of her operating room to another nearby building. Voropaev was impressed both by Goreva's fortitude and her beauty. They quickly became friends and soon others were talking about them as future husband and wife. But then Voropaev received his fourth wound, and it was Goreva who cut off his leg. From that point on, Voropaev could never picture himself as anything other than her patient, certainly not her husband. He knew he had to seek a new life, and this is what compelled him on his journey south.

Thinking of the difficulties awaiting him, Voropaev becomes fearful and doubts his strength. And for the first time, he regrets that he had remained alive.

Voropaev arrives at the Pobeda sovkhoz, a large vineyard, winery, and wine research institute. The wine expert, old Shirokogorov, is delivering one of his weekly lectures, answering random questions from the audience. Voropaev finds the lecture fascinating, including the information about the collection of medicinal herbs by school children and Young Pioneers.

|

|

In the morning, Chumandrin points out a nice house Voropaev can have if he comes to work for the sovkhoz. Voropaev is tempted, but declines, feeling that he is honor-bound to continue working for Korytov. Chumandrin says he'll keep the house vacant in case Vorobaev changes his mind.

CHAPTER TWO

Voropaev attends a meeting of the Pervomaisky kolkhoz. The chairman holds up a batch of medical certificates excusing the receipients from heavy work. He tearfully pleads with everyone to turn out and hoe the vines, since it's almost too late. In desperation, the chairman asks Voropaev to speak.

|

|

Voropaev declares the kolkhoz in a state of emergency. He says the war veterans should organize and lead the assault. Sick leave only for the dead! Thus working the crowd up into a patriotic frenzy, Voropaev leads them outside into the night where they immediately begin hoeing. This night expedition enabled the people to see in themselves something they had rarely seen before; and this seemed to be the most imporant and valuable aspect of this mission, for, digging in the dark, the hoeing at this moment could not have been very efficient.

The next day, Voropaev visits the veterans who had not attended the previous night's meeting. First is the surly Boyarishnikov, who refuses to get involved in the kolkhoz. Voropaev then goes to see Yuri Podnebesko and his wife, Natalya. Both 20 years old, they are extemely poor. They both joined the army right out of school, Yuri as a sapper, and Natalya as a nurse. They both were wounded, became ill and were sent south to recouperate. Cursing Korytov for knowing no more about people than a corpse, Voropaev finds Yuri work as a night watchman, and Natalya is put in the vegetable brigade.

CHAPTER THREE

While Voropaev is gone, Sofia Ivanovna gets the house registered in Voropaev's name and undertakes major repairs, using the 500 rubles he left behind. The roof is repaired. She has a gardener plant roses, pomegranates, five fig trees, wisterias, and Alexandria Muscat vines. She finds the garden gates, which had been blown off in an explosion. She is unable to carry them back to the house herself, so she paints a note on them, claiming them as Voropaev's property.

After undertaking the "offensive" at the Pervomaisky kolkhoz, Voropaev, for the first time since his return from the front, felt that elation, pleasure and confidence that make a man happy. As the offensive reaches its height, Voropaev chances upon a boy playing in the woods, giving a pretend speech in imitation of Voropaev.

Voropaev thinks of his own son, Seryozha. The family caring for Seryozha is a good one, but, even so, Voropaev is jealous, frightened that perhaps his son is being weaned away from him.

At the end of his second week at the kolkhoz, Voropaev falls, severely hurting his wounded leg and chest. One of the more active workers, Varvara Ogarnova, wants to take him to the doctor (the same doctor Voropaev ridiculed at the open meeting). Voropaev is reluctant, so she suggests taking him to a local healer at the Kalinin kolzhoz, Opanas Ivanovich Tsimbal, a Cossack settler from Kuban. Voropaev is shocked--Tsimbal is an old acquaintance.

Mamaev Kurgan The most famous kurgan and memorial arising from the Great Patriotic War. |

Voropaev arrives at Tsimbal's, and they renew their acquaintance. Unexpectedly for Voropaev, Dr. Komkov, the doctor Voropaev criticized at the meeting, arrives. Voropaev says if he had a doctor like Komkov at the front, he would have had him shot. Unfazed by Voropaev's criticism, Komkov goes on to say he's going to treat Voropaev's tuberculosis and very sensibly describes the treatment, consisting mainly of getting fresh air. In spite of himself, Voropaev finds himself developing some respect for Komkov, although he is reluctant to admit it. After Komkov leaves, Tsimbal says the doctor is a splendid and energetic man, and describes how he escaped from the Gestapo.

CHAPTER FOUR

To treat his tuberculosis, Voropaev spends days on end in Tsimbal's garden on a bed. Having never been alone with nature before, he is at first uncomfortable with it. But soon he grows accustomed to it. He takes particular note of the birds. Some of them were bird war victims--they limped, suffered from nervous twitches, or were deaf. Others were bird refugees, driven from their native habitats. Their attempts to unite with the local birds seemed so human.

Voropaev grows lonely. He recalls once a wounded man quoted Seneca to him, "A man is unhappy only to the degree that he thinks he is so." The same is true of courage, the man said, "There are no born cowards or born heroes. Every man becomes what it is easiest for him to become." Voropaev also remembers an observation of LaGrange to the effect that the wounds of victors heal faster than those of the vanquished. This Voropaev confirmed from his own experience. Although he received serious wounds, they magically stopped hurting as he marched victorious into liberated Bucharest and Sofia.

Voropaev often thinks of an early death, and he feels sad that, now that the war is ending and a wonderful life is about to begin, he will not be a part of it. Not his wounds, nor his diseased lung, but the consciousness of his uselessness tormented him. Komkov advises him not to wallow in his own misery, but to occupy himself with other people.

|

|

Svetlana had been conscripted to work in a German shell factory. She grew very depressed and descended into an animallike existence. She was chosen by a German as his mistress. She did not resist. Nor did she resist when this German passed her on to another. And now, Svetlana tearfully relates, she's pregnant and doesn't know what to do. Voropaev says he'll think about their situation and that they should call again in a few days. He wants to help Anya, but is unmoved by Svetlana.

An ex-sergeant, Gorodtsov, shows up. He was wounded in both legs in Hungary and was only recently discharged from the hospital. During the war, his wife and mother moved to this region, so he is now trying to decide what work to take up and has come to consult with Voropaev, a responsible neighbor.

It turns out that Voropaev and Gorodtsov fought in many of the same battles. They share war reminiscences, then Gorodtsov decribes how he saw Stalin twice! The first time was near Klin, when Gorodtsov was given the task of collecting the bodies of Germans after a battle. Several cars drove up, and out stepped Stalin. A talkative fellow working in the detail tells Stalin that he swore an oath to kill every German, which was at odds with the order to take prisoners. The fellow confesses that he fulfilled his oath and disobeyed the order. Stalin laughed and said that he would see that this fellow's case be considered an exception.

The second meeting took place in Stalingrad itself. One night, Gorodtsov was at a post about 50 paces away from the Germans. Three men approach--one of them is Stalin. He stands at a machine gun emplacement and gazes out at the city. Gorodtsov is afraid that the Germans will see Stalin and shoot him. Although he remains silent, Gorodtsov wants to shout out, "Go away, Comrade Stalin! We'll manage without you!" Sure enough, the Germans start firing. Gorodtsov shouts, "Hurrah!", and leads a charge. They overrun the German positions and look back to see Stalin waving his hat at them.

On another day, Lena arrives to visit Voropaev. She brings him a parcel from her mother. Voropaev says as soon as he gets better he'll return and help Sofia Ivanovna with the house repairs. Voropaev realizes that life is hard for Lena, too. He hopes that somehow he can help make her life easier and simpler. He thinks, "It is nice when there are people in the world whom you want to help."

A social club is formed and holds its first meeting at Tsimbal's, owing to the fact that Voropaev can't get around. Voropaev introduces Anya as the featured speaker. She delivers a moving talk about her experiences. Afterwords, others talk about their hopes, plans, and projects. A good time is had by all. Nothing of great moment, happened; it was just some people getting together to have a talk. But that is just what people lacked and what they craved. So it was a great success.

Voropaev becames something of a talking statue who could be trusted to relay messages because he had nothing to do and was always on the spot. He had almost no time to think about death now. People came to him with complaints, told him what progress they were making, asked for advice. He wrote letters to people at the front and wrote articles for the regional newspaper. Although he wasn't supposed to find out, he learned that the people of the kolkhoz secretly decided to build him a cottage right next to Tsimbal's house.

|

|

On New Year's Eve, Varvara comes to Tsimbal's house with Voropaev's rations and mail. She sees Tsimbal hacking away at Voropaev's wooden leg with an axe while Voropaev hops around on one leg, bitterly complaining. Varvara wryly calls out, "Fight to a victorious finish!" then asks what's going on. It seems Voropaev wanted to return to work, but Tsimbal is destroying the leg to prevent this.

Delivering the potatoes and mail, Varvara says she's seen Lena and approves of her as a perfect match for Voropaev. She advises Voropaev to move in with Lena right away and his life will improve. Voropaev is much vexed at this matchmaking. He instead wants to hear the news from the District Committee and the Pervomaisky kolkhoz. He incautiously admits to Varvara that things are bad on the Kalinin kolkhoz and he does not know who to rely on here. Varava reminds him that he knew none of them on the Perevomaisky kolkhoz when he whipped them up to action.

|

|

On behalf of the entire community, Tsimbal presents Voropaev with a New Year's present: a brand new wooden leg they had made specially for him. (That's why Tsimbal was chopping up the old leg earlier.)

|

|

At the sanitorium, there is a large, decorated fir tree, and children in all sorts of costumes, made with the simplest of materials. It is all so touching, so charming, and so poverty-stricken. Voropaev wants to shout, "To hell with wealth!"

Merezhkova leads Voropaev into a room to meet her philosophers. Voropaev had not been forewarned, so he winces when he sees the children in the room: Zina Kuzminskaya, a 13-year-old girl from Smolensk whose fingers were chopped off by the Germans when she refused to say where her father's partisan detachment was; Shura Naidenov, a roly-poly, who lost both arms and both legs in an air raid; Petya Bunchikov, who lost his legs in a mine field; and Lyonechka Kovrov, who lost his eyesight in an air raid. One thing these children miss is a happy face. Even when happy people come to visit, they become sad when they enter the room. Voropaev is greatly moved by these children and realizes that in this room one cannot utter even a single word of untruth. He convinces the children to forget their embarrassment and join the others at the party. He has their beds wheeled out into the main room, and they are soon enjoying themselves like everyone else. Shura declaims a poem. Everyone is impressed with his determination--he wants to become a scientist to show the Germans what Russians can do, even without arms and legs.

|

|

CHAPTER SIX

By February 1945, Voropaev is recovered and back living with Lena and Sofia Ivanovna. His relations with Sofia Ivanovna are somewhat tense. One evening, he decides to skip a District Party Committee meeting to stay home and have a talk alone with her. She ennumerates how she thinks repairs should proceed and also wants to build a pigsty and hen house to collect potash and maure. All of this, she says, can be used for trading, to make money. They get into a very heated argument and Voropaev promises to ruthlessly check her every attempt to become a market woman. They are on the brink of a complete break when Lena bursts in. She says something important is happening at the Party meeting and that Voropaev must come immediately.

While walking to the meeting, Voropaev decides that it makes senses, so he asks Lena to live with him as husband and wife. She is taken aback. While not agreeing, she does not reject the proposal outright.

At the meeting it is revealed that important visitors are expected from Moscow, England, and America. Voropaev is appointed supernumerary interpreter in exceptional cases of city-wide importance. Korytov says Voropaev must take up quarters in the city so that he can be found immediately when needed. An unknown Major from the State Security Service tests Voropaev's English and is satisfied. He says Voropaev will probably not be called upon for anything exceptionally important, except if the Americans and English start a scrap with each other, then Voropaev will have to pacify them.

Everyone is very excited. The District Party members pepper Voropaev with questions, such as, do Americans eat salt herring with onions and if it's proper to offer them tea. Shirokogorov is worried that the foreigners might want to visit the sovkhoz wine cellar--he doesn't like that idea. Stoiko, chairman of the Novoselo kolkhoz, is worried about what to do if Stalin comes to visit. Surely he couldn't take Stalin to his office...he has chickens in there!

|

The British gave Voropaev the impression of being sincerely amazed to find that the world was inhabited by others besides themselves, and that these others were human. Willingly admitting that the Russians are brave, the Norwegians pious, the Spaniards hotheaded and the Belgians prudent, they envied none, regarding themselves as superior to all. The Americans created the impression of being jolly good fellows who hated only two nations--the Japanese and the British." |

Soon, foreign ships appear in port, and American and British sailors appear in town. They crowd the town's only restaurant where Russian cocktails--a blend of vodka and beer--rouse universal admiration. Voropaev is constantly breaking up arguments between the Americans and the British over who is braver.

Then it is learned that Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill have arrived. Roosevelt creates a good impression on those who see him, identifying him as a man of great zeal. However, Churchill is obese and senile-looking, giving the impression of an old gentleman who has lunched well and washed his lunch down with some delicious and bracing beverage.

Voropaev gets a call to go to the Pervomaisky kolkhoz where some drunken American is going from house to house asking idiotic questions.

The drunken American turns out to be Harris, a famous reporter. After sleeping it off a bit, Harris turns out to be a likeable fellow. He and Voropaev get into a series of heated, yet friendly arguements. Harris insists that America has the monopoly on democracy. Americans like and respect anything that resembles America; anything remote, they reject.

Voropaev and Harris go to see Shirokogorov. Shirokogorov offers the opinion that victory could be won this year if the Americans and British did not hinder it; but, says Shirokogorov, the Americans and British are unprepared for victory. The Soviets have pushed the victory so near to the U.S. and Britain that they only need reach out an grab it, but, the old man continues, the U.S. and Britain are afraid that people will say they got victory as a present from the Soviets.

They retire to the wine-tasting room. Shirokogorov waxes poetic about the fragrances, shades, subtlties, and inspirations of the wines. All Harris does is gulp down glass after glass, indiscriminately mixing wines. Harris wants to know why Shirokogorov is messing about with wines while his country is in ruins. Shirokogorov says he is preparing an elixir of triumph, wines of victory, repose, and comfort. In response to a question, Shirokogorov says that while German fascism may soon be crushed, Harris and many like him will rush in to be the fierest champions of capitalism in its worst forms. However, Roosevelt may some day come over to the Soviet side. He dismisses the importance of England, saying Churchill's England is like America's kept woman.

Voropaev takes Harris to meet the "philosophers" at the children's sanitarium. Harris gets one look at the armless, legless Shura and wants to know why he is not immediately killed. Voropaev explains that Shura is no less human than they are, but Harris refuses to accept this and storms out of the room.

On the drive back to town, the chauffeur points out to Harris a well into which the Germans threw his two young nephews. One died of hunger, the other's head was smashed. Harris says these things should not be spoken of out loud.

Voropaev says that while, on the whole, Russians like Americans, it is apparent that America is pursuing the policy of a degenerate nation. Many American capitalists just want to grab the fruits of victory for themselves. The bankers want to turn America into a stronghold of mililtarism with Churchill as their god. Roosevelt is too good a President for these bankers; they deserve much worse.

|

|

Voropaev and Vasyutin check out the landscape, deciding on the best place for the future sovkhoz offices. They also visit a bay which Voropaev has named Happy Bay and imagine a future health resort on the site. Voropaev tells Vasyutin that he has a theory. Just as before, when they took people from the villages and factories and moved them forward into the capital and People's Commissariats, now they should take the cadres that have been trained at the top and bring them down to lead the practical work in the villages and factories. Vasyutin doesn't much like the idea. He also scornfully recalls a memorandum from Zarubin suggesting the construction of a home for composers on the mountain ridge because, he said, there's a lot of music there that's going to waste.

Voropaev thinks that he will soon get in the harness, but where the Podneneskos and Anya Stupina need him, not where Vasyutin wants him.

The next day, Voropaev joins Harris and the other foreign journalists on their bus tour. They pass a burned-out tank. Voropaev tells about Chernykh's brigade and their part in the liberation of the area. The journalists have no interest in the story. Instead, they ask if Stalin has been to Sevastopol. Voropaev says no one should be allowed in Sevastopol because it is thick with mines. The English journalist haughtily announces that they will go wherever they want and only to the places they want.

|

Great Leap Forward with:  Vaslav "Twinkle-Toes" Nijinsky |

The journalists stop for breakfast and cognac. Harris says his first success as a journalist came writing about the Nijinsky performace of Prince Igor in Paris. The frenzied mass dancing, Harris says, gave him insight into the Russian soul. His conclusion was that Russian art, with tremendous strain, was restraining the passion of its people for a great leap forward, and all of this he connects to Russian history and politics. Voropaev says that to study a country from its ballet is like studying fruit-growing by eating jam. It would be more instructive to read Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Gorky, not to mention Lenin. Or, better yet, the Russian soul was best revealed in the 9-hour battle for Sapun Hill right here, or in Stalingrad.

They journalists decide they don't want to discuss or analyze events. All they want to do is see monuments. Voropaev says there are no special monuments yet, but that the entire city is a monument. Harris ridicules this idea. The journalists go see the old English Cemetery of 1855.

PART TWO

CHAPTER SEVEN

Voropaev is bidding farewell to some tipsy American sailors when an old acquaintance, Lieutenant-General Roman Ilych Romanenko drives up. Romanenko is suprised to find Voropaev out of the army and in this backwaters. Somewhat condescendingly, he he suggests that Voropaev should rejoin the army and come work with him at the General Staff in Moscow.

Romanenko takes Voropaev to lunch...to the villa where the Soviet delegation is quartered. They dine with generals and diplomats all of whom, contrary to Romanenko, support Voropaev's decision to work among the people. Voropaev is not jealous of these generals and diplomats, who would travel abroad and have lives rich in diverse impressions. He felt his descent to the sources of life and human strength was not because he was being degraded, but rather it was a preparation for a new leap upward.

The next day, Romanenko picks up Voropaev to take him back to the villa. On the road, they pass a little girl, Lena Tvorozhenkova, who is holding some flowers that she dreams of giving to Stalin. Instead, she gives them to Voropaev.

At the villa, a general formally invites Voropaev to rejoin the service and move to Moscow. Voropaev politely rejects the idea, feeling that he can make important contributions to the Party active here.

|

Stalin is talking with the gardener, advising him to ignore the laws of established science and to create grapes and lemons that will grow in the severe northern climates.

Stalin shakes Voropaev's hand and gently chides him for leading assaults at the kolkhozes. But, Stalin says, Voropaev did the right thing by refusing the transfer to Moscow. There are still too many people, Stalin says, who prefer to remain officials in Moscow rather than be leaders in the provinces. But their time will end soon, Stalin promises.

Stalin then asks what are the most urgent needs in the district. Voropaev says they need clever people. Stalin orders Voropaev to make clever people here on the spot and not expect then to come raining down on him from Moscow. "Nowhere is it written the clever workers are born only in Moscow," Stalin reminds him.

Recognizing that life is hard for the people, Stalin promises that soon the Party will grapple with the food problem with the same energy as it grappled with industrialization.

Stalin in greatly interested in Voropaev's assessment of the various people in the district such as Anya Stupina, the Podnebeksos, Gorodtsov, Tsimbal, and others. Stalin makes comments on all the people mentioned, but is particuarly taken with the story of Gorodtsov, who dreams of wheat. Stalin gives Voropaev a message for Gorodtsov. He is to tell the ex-soldier that those here in this region are in the second echelon, in reserve, as it were. Once the nation has solved the wheat problem, Stalin says, they will address the local problems here.

Stalin notices the flowers in Voropaev's pocket. Voropaev tells him about the little girl who dreamed of giving the flowers to the great leader. Stalin accepts the flowers and gives Voropaev a basket of pastries to give to the girl. At the end of the meeting, Stalin again says that Voropaev did the right thing by deciding to stay in the district.

Returning home, Voropaev tells Lena about the meeting and says he feels a thousand years younger. The next day, Voropaev tells Korytov. Korytov is envious and says that since it was a private meeting, not an official one, they should not discuss it publicly. Voropaev disagrees, but says he'll think it over.

But word of Voropaev's meeting with Stalin gets out. Soon everyone crowds into his home, demanding to hear the story. Everyone is excited to hear what Stalin had said about each of them personally. But they are also worried and terrified. Stalin knows their names. What if he orders an investigation? They had really better get to work now and show results!

CHAPTER EIGHT

In the beginning of April, Goreva is with the Third Ukrainian army as it moves in to begin the assault on Vienna. She is riding forward to establish a field hospital in the suburb of Simmering. The path is blocked by a large crowd of Russian officers. Goreva gets out and sees that the officers, along with an accordionist and photography or cinematographer, are gathered around Strauss' grave, which has been freshly bedecked with flowers.

As the battle for Vienna rages, Goreva moves into the city, dodging snipers and setting up field dressing stations in apartments. She is summoned to examine Golyshev, a wounded regimental Commander who is refusing evacuation to a hospital. When Goreva arrives at the command post, the young surgeon in attendance reports that Golychev received a shell splinter in the lung. Goreva, however, can see that the splinter has not entered the lung, but is stuck between the ribs. She agrees with Golyshev that he need not be evacuated, especially when victory is so near at hand.

That night at the command post, Goreva and the officers discuss the operation and the damage done to the city. The subject of Voropaev comes up. The officers are incredulous to hear that he has taken up farming. Golyshev comments that it's time for Voropaev and Goreva to get married.

|

|

Back at the field administration, Goreva is billeted with an Austrian family named Altman. They invite her for tea in the evening. All the Altmans want to know about is the fashions in the various countries Goreva's been through.

|

Russo-Austrian Army:  Mikhail I. Kutuzov |

Frau Altman expects Goreva to say Vienna is the most beautiful city in the world. But actually, Goreva prefers Riga, Vilnius, Lvov, and Leningrad. Goreva was disappointed with her impressions and realizes that the chief thing about a city is not its architecture but its people. A deserted, depopulated city is alway ugly and dreary.

|

|

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN