presents a detailed summary of:

THE

IRON FLOOD

by Aleksandr Serafimovich

(1924)

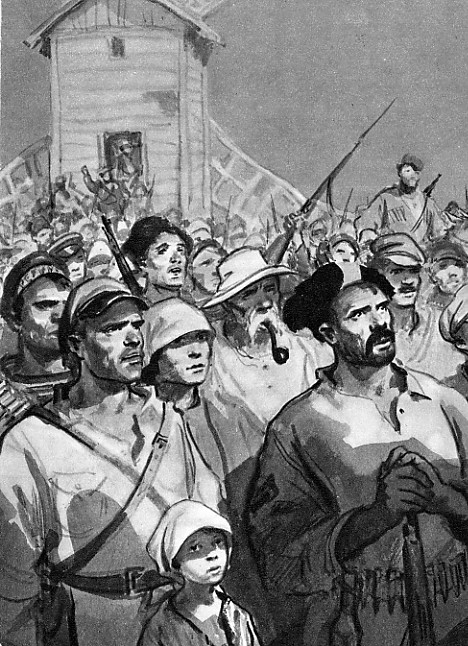

1. The disorderly rabble of a Red Army unit is camped in a Cossack village. Mixed in with the guns and ammunition carts are crying babies and suckling mothers. Diapers hang from rifles to dry.

The Cossacks themselves are all gone, leaving behind only the Cossack women, who sneer and hiss at the Reds.

2. Vorobyov, the regimental commander, surrounded by the rest of the command staff, tries to address the restive army. But he is shouted down, accused of incompetence and betrayal, of having led them into a trap.

One of the commanders, seemingly made of lead, with a square, iron jaw, speaks to the crowd, reminding them that he is one of them, a toiler who rose through the ranks. He beseeches them to stop this unruly behavior. The situation is cricital, he notes. Cossacks are pressing in on all sides and every moment counts.

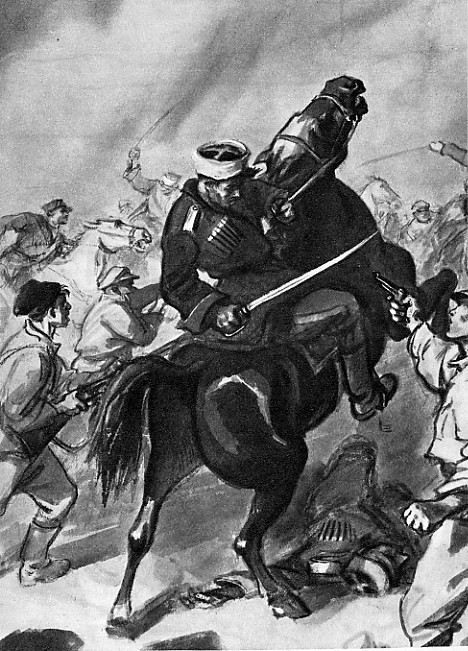

A tall man in a sailor's cap lunges with a bayonet at the man with the iron jaw, who is named Kozhukh. The tall man is jostled, however, and instead, his bayonet slices into the belly of a young batallion commander. The soldiers are about to murder all the commanders, but they are distracted as they see two riders approaching at top speed.

The first horse arrives and its rider, dead, slides off. It is Okhrim from Pavlovskaya. The second rider is Okhrim's father, Pavlo. He reports that the Cossacks are revolting in practically every nearby village. The Reds and Red-sympathizers are being hacked to pieces and hung from gallows.

|

|

As his first order, Kozhukh commands that Okhrim and the young batallion commander be buried. At the ceremony, Kozhukh says that they are being attacked by landlords, capitalists, blood-suckers, and scoundrels. But, he says, with the power of the workers and peasants, Soviet Russia will live till the end of time.

3. That night, Kozhukh and his staff pore over the map, trying to find a way out of this trap: to the west, the sea; to the north and east, hostile villages and farms; to the south, seemingly impassable mountains. The commanders--each thinking himself smarter than the others--all offer conflicting opinions. One suggests that they separate the army from the thousands of refugee carts which are tagging along. Kozhukh reminds him that every soldier has a relative among the refugees and if the army were to abandon them, surely the soldiers would desert.

Outside, gunshots are heard. Kozhukh sends comrade Aleksei Prikhodko, a Kuban Cossack, to investigate.

Kozhukh decides that they will march south over the mountains, hoping to rejoin their main forces along the way. The commanders are silent, but they all think Kozhukh is a fool.

4. As Aleksei moves among the sleeping camp, he comes upon a beautiful young peasant woman named Anka. She demonstrates how she will kill herself if captured by the Cossacks.

Aleksei thinks it would be very easy to marry Anka. But, still, he wants to hold out for the idealized, educated beauty he's always imagined for himself. That doesn't stop him, however, from taking Anka by the elbow and asking her to go off to the orchard with him. Anka playfully shoves Aleksei away and jumps into her cart, awakening her Granny Gorpina, who's sleeping there.

Granny Gorpina begins complaining, saying the Bolsheviks did some good by getting rid of the landowners and that cur of a tsar, but now she's lost everything. Let Soviet power vanish, she says. But, before drifting off to sleep again, Granny Gorpina says a prayer to God asking him to give the Bolsheviks strength, despite their disbelief in heaven.

5. At dawn, the refugees and rag-tag army begin crossing the bridge over the river. Cossacks attack from the rear. A soldier whom the Cossacks caught and tortured is released. Written in blood on his chest is: "This is how we shall treat all you Bolshevik swine."

Fighting begins amid the peasants and refugees on the bridge. Carts and livestock become hopelessly mixed up. Passage is completely blocked. Pandemonium reigns. Kozhukh rushes up and shouts orders, but no one listens. To get everyone's attention, he shoots and kills the nearest horse. The peasants turn on Kozhukh, ready to kill him. He fires several bursts of a machine gun over their heads, and they fall back.

Kozhukh leaves the machine gun and starts to abuse the peasants at the top of his voice. They submit to his authority. He clears the bridge. Some carts, inextricably locked together, are tossed into the river. Soldiers are posted to make sure movement continues over the bridge.

|

|

The Reds manage to cross the river and burn the bridge behind them.

Cossack Web Cossack history, songs, photos, links, etc. |

But then, following the Revolution, aliens and Cossacks embraced each other as equals, as citizens. All understood now what "landlords", "bourgeois" and "atamans" meant. Tsarist officers were beheaded or put in sacks and tossed into the river.

Planting time came. The cry went out to divide up the land. But this the Cossacks could not abide. The aliens again became "Satan's offal" and "filthy intruders." The Cossacks stopped killing the generals and officers.

7. As the Red soldiers--their faces bloodied, bruised and swollen--march along, they brag about how they beat up the Cossacks. Some Cossack prisoners admit they were drunk during the battle. Their officers had discovered a cache of vodka and distributed two bottles to every Cosack to get them riled up for the fight.

Kozhukh looks at the undisciplined, roaring torrent that is is army. The troops are mainly demobilized soldiers from the tsarist army. In civilian life they were small craftsmen, coopers, locksmiths, tinkers, carpenters, cobblers, barbers and--more numerous than others--fishermen. These were "aliens".

Kozhukh looks at the undisciplined, roaring torrent that is is army. The troops are mainly demobilized soldiers from the tsarist army. In civilian life they were small craftsmen, coopers, locksmiths, tinkers, carpenters, cobblers, barbers and--more numerous than others--fishermen. These were "aliens".There were also some revolutionary Cossacks among them. In long Circassian coats, astride sturdy horses, there were the only disciplined part of this ragged, disorderly, pouring stream.

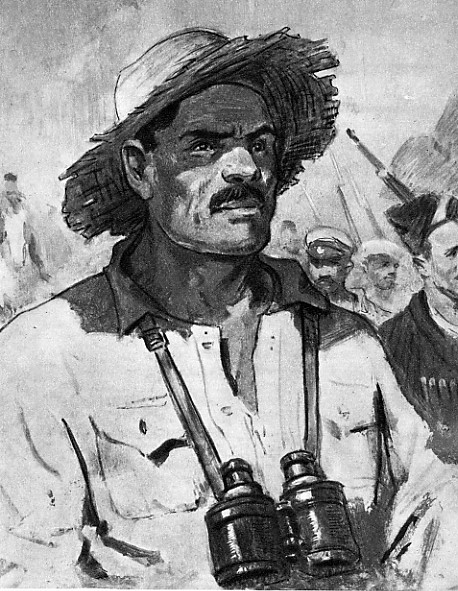

Kozhukh himself was born an alien in a dirt-poor family. At age six, he was sent to work as a shepherd. Later, as a bright lad, a kulak hired him to work in a shop. He taught himself to read and write.

When the war came, Kozhukh was sent to the Turkish front, where he became a crack machine-gunner. Brave, disciplined, and able, he was sent to officers training school. The teachers there laughed at him--a muzhik, a brainless brute trying to become an officer! Naturally, they flunked him. Three times Kozhukh was went to the school, and three times they flunked him. But headquarters, desperate for officers, promoted Kozhukh to ensign anyway.

Kozhukh was proud of his should straps, but also a bit sad because they put him apart from the ordinary soldier. And, of course, none of the other officers would accept him as an equal.

Then the Revolution came. Kozhukh listened to the orators and understood. He regretted his shoulder straps, because they marked him as an enemy of the people. He ripped them off and returned to his village, determined to fight in the service of the poor masses.

In the village, anyone with two pairs of trousers was suspected of being bourgeois. So it was that the poor peasants helped themselve to everything in Kozhukh's cottage, leaving him and his wife with only the clothes on their backs.

8. The tens of thousands of Red troops and refugees reach the foot of the mountains. Confusion reigns as Cossacks harrass from the rear. Kozhukh declares that their one chance is to cross the mountains, make a forced march along the coast, then cross back onto the steppe and join up with the main force. Another commander named Smolokurov says they should stay and defend themselves honorably, not run. He threatens to open fire on Kozhukh's column if he attempts to cross the mountains.

A half hour later, Kozhukh's column sets out. No one dares hinder it. In fact, everyone follows. Those who get in the way are thrown into ditches.

Read a summary of another classic of Socialist Realism: Fyodor Gladkov's Cement |

The destroyer opens fire. The horse pulling Anka and Granny Gorpina's cart is spooked. It jumps, breaking both shafts of the cart. The horse is shot and dumped into a ditch with the cart, so that the column can keep moving. Weeping, Granny Gorpina and Anka retrieve what they can from the cart.

Some Cossacks appear on the top of the mountain with four cannon. They begin firing down at the fleeing Reds. The German commandant is greatly offended. Women and children are to be killed only with his permission. So the German destroyer aims its guns at the Cossack artillery. The Cossacks return fire, and the destroyer chugs out further to sea, out of range.

As the Red column keeps moving through town, hoards of crippled and wounded soldiers pour out of the hospitals, begging to be taken along. But with so many of their own wounded and with limited supplies, the Reds can't comply.

10. All through the day and the next night they march. As dawn breaks again, people begin to stagger. Cursing becomes general. They called Kozhukh a madman. During the night, two of Smolokurov's columns had stopped to rest, and now there was a break of some ten versts between the marchers.

That night, they finally stop. One might have expected everyone to fall dead asleep. But instead, lively crowds gather around fires and boiling kettles. There is laughter and the sound of accordions.

11. A young mother still clutches the infant which died during the German artillery attack. Women try to persuade her to bury the child. The mother won't listen and keeps putting her swollen breast into the dead child's mouth. Men try to yank the baby away, but the mother screams and bites, protecting her child. A messenger is sent to fetch Stepan, the woman's husband, who is with the troops.

12. At other campfires, sailors sing, drink, and curse. Mandolins, guitars, and balalaikas sound out. And they grumble about Kozhukh, saying he acts like all officers--enemies and exploiters of the toiling masses.

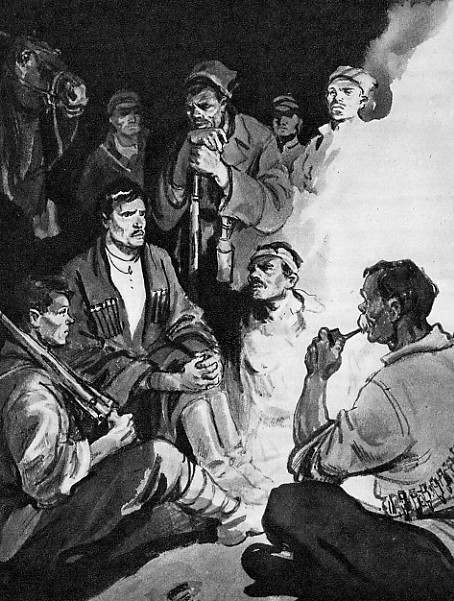

13. At another campfire, Pavlo--he who lost his son Okhrim--sits, holding his knees, with his horse behind him. He is dressed as a Cossack and was able to move among them. He tells what he saw in the town after the Red column left and the Cossacks entered. The sailors remaining in town were ordered to dig their own graves. Those who did not dig fast enough were shot in the belly to make sure they suffered as much as possible. A nurse who stayed to tend to the wounded was raped by a hundred Cossacks, and she died under them. All the wounded soldiers--20,000 of them--were killed--either sliced with a sword or thrown from the windows to smash on the pavement below.

13. At another campfire, Pavlo--he who lost his son Okhrim--sits, holding his knees, with his horse behind him. He is dressed as a Cossack and was able to move among them. He tells what he saw in the town after the Red column left and the Cossacks entered. The sailors remaining in town were ordered to dig their own graves. Those who did not dig fast enough were shot in the belly to make sure they suffered as much as possible. A nurse who stayed to tend to the wounded was raped by a hundred Cossacks, and she died under them. All the wounded soldiers--20,000 of them--were killed--either sliced with a sword or thrown from the windows to smash on the pavement below.Those listening knew Pavlo's personal story--his 12-year-old son's head was crushed by Cossack rifle butts; his mother lashed to death; his wife raped repeatedly and hanged.

Pavlo gets on his horse and goes to report what he knows to Kozhukh.

14. Sailors, with revolvers and bombs on their belts, come up to a group of soldiers. It was the sailors, they boast, who started the Revolution; sailors who brought literature from abroad and who were shot and drowned by the tsar for it; sailors who killed the bourgeois and the priests; sailors who fought for the Revolution while the soldiers were still helping the tsar with their bayonets.

Insults continue. The scene starts to get ugly. Soldiers and sailors take out and cock their weapons. An old soldier continues sipping his soup and call the sailors crows and cockerels. This defuses the situation somewhat. The sailors put away their guns, saying that the soldiers aren't worth it. They criticize the soldiers for being sheep, blindly following Kozhukh, whom they denigrate as a damned ex-tsarist officer who ought to be shot.

The sailors leave. The soldiers start to grumble that perhaps the sailors were right about Kozhukh. And, they wonder, why does the Soviet government do nothing to help them?

15 & 16. Finally, the camp fires die out, and everyone goes to sleep. A lone dark figure hurries past the prone bodies. It is Stepan. He finds his wife, who hands him their dead baby. For the first time since the death, the mother weeps. Men dig a grave for the baby, while the women suck on the mother's engorged breasts and spit the milk to the ground.

17. As most of the camp sleeps, Kozhukh pores over the map. He summons the commanders and chastizes them for not obeying orders. The commanders all protest that Kozhukh is driving the men too hard and will ruin the army if he keeps on like this. The professional officers from the old army all think Kozhukh an ignorant bumpkin. The new officers think that Kozhukh is just one of them, and each one thinks he could do better.

Solider-representatives of each of the companies then crowd into the room. Kozhukh sums up the dire situation and says that the only way to avoid destruction to is follow the coast to Tuapse, then cross the mountains and descend into the Kuban where they can rejoin the main forces.

|

|

A scout reports that the second and third columns halted for the night some ten versts behind them and have sent word that Kozhukh should wait for them. He further reports that the sailors are spreading sedition, saying that Kozhukh should be killed.

Kozhukh orders the commanders to get ready to begin the march in an hour. Further, he orders that the sailors be driven out of the ranks. They can march with the lagging columns if they like. He gives permission for machine guns to be used against the sailors if necessary.

18. The second and third columns continue to lag. At night, the sailors kicked out of Kozhukh's column continue their seditious grumblings, calling the soldiers ignornat riffraff and saying nasty things about Kozhukh. The sailors also heap scorn on the Bolsheviks, asserting that their leaders sold Russia to the kaiser for a train load of gold.

Among themselves, the soldiers says that although the sailors are windbags, they do have a valid point.

The command staffs of the second and third columns hold a meeting and decide to elect a chief for the whole army. They all vote for Smolokurov--although each commander secretly assumes that Smolokurov will screw up, giving him the chance to take over.

Orders are sent out to the soldiers. The troops listen eagerly to the reading, then fight over the papers, so they can use them to roll cigarettes.

Smolokurov sends an order to Kozhukh demanding that he halt is march and report to Smolokurov immediately. Kozhukh ignores the order.

The commanders convince Smolokurov to abandon the coast route and cross the mountains immediately. The chief of staff quietly points out to Smolokurov that they will surely lose their baggage train and artillery on the narrow mountain path. So Smolokurov changes his mind, and they press on forward.

19. Kozhukh's column stops for the night, and he goes to sleep in a cart. The rowdy sailors approach, awakening Kozhukh. They demand food. Kozhukh tells them to join the army, then they will receive the meager army ration. The sailors respond that Kozhukh has no right to dictate to them. They creep up on Kozhukh, intending to attack him, but Kozhukh quickly fires a machine gun over their heads, stopping them.

20. The column marches on through a village full of Greeks. The Greeks claim they have no food, so the soldiers confiscate all the goats. Next they come upon a Russian village. The Russians generously share their food. When leaving, the soldiers confiscate the chickens, geese, and ducks.

In an abandoned villa they find a gramaphone and many records. They play the music as they march along. But one record--"God Save the Tsar", quickly gets smashed under a hundred boot heels.

21-22. The column comes to a halt. Up ahead is a narrow bridge over a foaming mountain stream. The bridge is guarded by Georgian Mensheviks with machine guns and cannons.

Half of Kozhukh's men have no ammunition at all. And he has only one cannon with sixteen shells. He orders the cavalry to attack the bridge. The cavalry know that it is a suicide mission, but they vow to do it nonetheless.

Kozhukh's cannon begins firing on the Georgian position. The Georgians are startled by the cavalry's foolhearty attack. As the sixteenth and final shell explodes, the cavalry is across the bridge! The main Georgian units retreat. Georgian officers abandon their troops who are slashed to bits. Victory for the Reds!

23. The column continues along the high road until it emerges in a narrow gorge. Gerogia troops have taken up positions on a mountain side directly opposite the gorge. As the Reds come into view, the Georgias open fire with machine guns and artillery, forcing Kozhukh's troops to pull back. Georgian steamers are in the bay by the distant town. The situation is hopeless.

Two soldiers come up to Kozhukh, and he can see that they are drunk. They say they were reconnoitering and came upon a Georgian tavern, where some Georgians were drinking wine and eating shashlik. They killed all but two of the Georgians and ate the shashlik...but never touched the wine they claim. While bringing back the hostages, they came upon local Russians who told them about some winding, difficult foot paths which can be used to bypass the town.

Kozhukh orders that the squadrons must take the foot paths, sneak into the enemy camp and seize it...without firing a shot...because they have no ammunition. The infantry regiment is to go down to the sea, climb over the rocks to the port, and, at dawn, seize the moored steamers without firing a shot. Kozhukh himself plans to lead a frontal assault through the gorge. They have no bullets or shells for their cannon, but, in a rousing speech, Kozhukh assures the troops that "If we all rush like one, the road to our own people is open!"

24. Prince Mikheladze, dressed smartly in a fine Circassian coat and elegant fur hat, is in command of the Georgian forces. He himself is a socialist, but he can't stand those--like the Bolsheviks--who fan the flames of the lowest passions of the masses in the guise of socialism. His plan is for the steamers in the bay to open fire on the rear of the enemy while he blasts away from the front.

An orderly tells Mikheladze that dinner is ready. He passes by his hungry troops who are surviving on a handful of maize a day. In his tent, Mikheladze and the other officers dine on caviar, cheese, fruits, and fine wines.

25. In the pitch-black night, a Georgian sentry paces back and forth on the edge of a precipice that is so steep not even a lizard could scale it.

The sentry feels that the Bolsheviks have done him no harm. They got rid of the tsar, who was an enemy of Georgia, and they even talk about giving land to the peasants. Still, he will follow orders and shoot at them tomorrow.

He fights off drowsiness, dreaming of his wife and infant son. Suddenly, Red soldiers emerge from the blackness and attack.

26. Red soldiers flood into the Georgian camp, smashing skulls with rifle butts and doing deadly work with bayonets. Mikheladze flees in terror. He realizes now that life itself is the most precious thing. He would agree to do anything for the Bolsheviks--tend their cattle, cart their manure--if only they would spare him.

Mikheladze runs to the harbor, thinking to make his escape on a steamer. But there he sees the same horror--Reds slaughtering Georgians. He dashes through the streets of the town searching desperately for refuge, but all doors are closed to him. The Red cavalry gallops past and kills Mikheladze.

27. After the town is captured, the troops--particularly the sailors--burst into a frenzy of looting. They cast off their rags and put on whatever they can grab from the shops. When there are no more new trousers, one soldier puts on several pairs of women's knickers, even though he can't figure out why anyone would make pants so thin.

The cavalry then gallops into the town square and starts whipping the looters.

28. Kozhukhk assembles the soldiers in the town square. They are all dressed in their ridiculous, mismatched outfits which they looted. Some in starched white shirts, some in absurdly small frock coats--and let's not forget those wearing women's bloomers.

Kozhukh orders the return of all looted goods, which will then be distributed to the women and children. He also orders that all looters will receive 25 lashes. The looters reluctantly, but submissively, step forward, ready to accept punishment. Seeing that his authority has been established, Kozhukh grants the guilty a reprieve.

|

|

A Georgia soldier is caught hiding in the bushes nearby. He is barely 16 years old and begs for mercy, saying he was drafted. The soldiers look at him sympathetically. Nonetheless, they carry out the commander's orders and shoot him.

30. The column sets out again, with a tremendous amount of booty: ample ammunition, cannons, fine horses, field telephones, barbed wire, medicines, ambulance carts, and new records for the gramaphone. But still they lack wheat and hay.

As they begin the mountain crossing, a raging, torrential rain storm strikes. Carts, with women and children, are swept away over the precipice never to be seen again. Men are struck with lightning. Scores of horses fall.

Afterwards, Kozhukh orders them to press on without rest. Exhausted and starving, horses collapse. Some women, with too many children to look after, leave their youngest on abandoned carts. Others, their breasts empty, clutch their beloved infants and watch while they die.

Someone puts a record on the gramaphone. Instead of a song, it is a recording of people laughing. The marchers smile, then begin to laugh themselves. The laughter ripples through the column far to the rear where they can't hear the gramaphone and have no idea why their laughing. Hearing the laughter, Kozhukh goes to investigate. He feels himself beginning to smile, but resolutely clenches his teeth. When he discovers the source of the laughter, he curses and whips the record off the gramaphone.

And just then...the top of the range is sighted!

31. As the column tramps along, they come upon a grizzley sight: the bodies of four naked men and one naked woman, hanging from posts, nooses around their necks. Ravens had pecked out their eyes and plucked out their greenish, slimy entrails. The woman's breasts had been cut off. The stench is nauseating. A note signed by General Pokrovsky, leader of the Cossack forces, nailed to one of the posts, proclaims that the same fate awaits anyone who has any type of intercourse with the Bolsheviks.

As the troops continue their march, they unconsciously put a determined swing in their step and increase their pace significantly.

As the refugees and baggage train move past the murdered comrades, one woman shreiks out, recognizing one of them as her son. She hysterically clutches at the cold feet and refuses to continue on. She is finally overpowered and tied to a cart.

32. General Pokrovsky's Cossacks lie in wait for the approaching Reds. The Cossacks have heard that they Reds are carrying trememdous riches which they have looted--gold, jewels, gramaphones--despite the fact that they are all bare-footed and in rags, which only proves their addiction to vagrancy and disorderly living.

As Kozhukh's troops emerge from the mountains, they clash with the Cossacks. The fighting is fierce, but the outcome is clear: the Cossacks are put to rout. The remnants of the Cossacks forces have to flee back to their entrenched positions.

As Kozhukh's troops emerge from the mountains, they clash with the Cossacks. The fighting is fierce, but the outcome is clear: the Cossacks are put to rout. The remnants of the Cossacks forces have to flee back to their entrenched positions. Kozhukh holds his forces back until night, then they again hurl themselves againt the Cossacks with diabolic fierceness. And again, the Reds are victorious. When the sun rises, the steppe is covered with Cossacks--none wounded, no prisoners...all dead.

When the dead Red troops are collected, the families in the baggage train want a priest to conduct a service, so that their loved ones won't be buried like dumb beasts. A priest is found and--threatened with being flayed alive--he sings a funeral service in a wonderful voice.

33. Kozhukh feels pleased. In his hands the army was an obidient, pliant instrument. The Cossacks hold positions in a village on on the other side of the Belaya River. Just before dawn, Kozhukh's troops race across the river and a battle rages again. Reds are mowed down in scores. Cossacks fall by the hundreds. Part of the Cossack headquarters staff is captured. They are beheaded near the priest's stable, and blood soaks the dung.

They search the house of the village ataman, but he is not there. They shout out that unless the ataman reveals himself, they will kill his family. Then they make good on the threat, slaughtering the children and spliting open the skull of his wife.

They learn that General Pokrovsky himself just managed to escape without any pants on an unsaddled horse. The Red troops are surprised to learn that "gentlemen" sleep without pants; the idea seems inhuman to them.

When the time comes to bury the dead, Kozhukh orders that a captured Cossack band play at the funeral service. Some women argue, insisting on a priest again, but in the end, the idea of the band wins out.

34. Kozhukh knows that he should immediately pursue the fleeing Cossacks, but he does not have the heart to abandon the lagging columns, knowing that they would never stand a chance on their own. So he waits for three days. Still no sign of the other columns.

During this time, the Cossacks are able to amass reinforcements. During the night, the Cossacks attack. A commander at the front line urgently calls Kozhukh on the field telephone begging for reinforcements. Kozhukh says there are none and orders the commander to fight on until the last man. The Cossacks break through the line. Kozhukh bumps into the commander who had, despite orders, withdrawn. Kozhukh orders the commander arrested.

Kozhukh races forward, mans a machine gun, and mows down Cossacks. The attack is beaten back. Ten Cossacks, stinking of vodka, are taken prisoner. The commander who disobeyed orders is shot.

35. At twilight, the Cossack cavalry charges at the refugees--old men, women, children, the wounded--in the rear of Kozhukh's column. Their aim is to spread panic. But these people do not flinch. Each one picks up what he or she can--a stick, a shaft, a pitchfork, a branch--and they march in their seemingly endless numbers right at the advancing Cossacks. Instinctively, without command, the Cossacks stop, turn, and flee.

35. At twilight, the Cossack cavalry charges at the refugees--old men, women, children, the wounded--in the rear of Kozhukh's column. Their aim is to spread panic. But these people do not flinch. Each one picks up what he or she can--a stick, a shaft, a pitchfork, a branch--and they march in their seemingly endless numbers right at the advancing Cossacks. Instinctively, without command, the Cossacks stop, turn, and flee.36. Deciding that he can wait no longer for the lagging columns, Kozhukh plans a night attack: an artillery barrage on the Cossack trenches, followed by a general assault. About a half hour before the attack is scheduled, Kozhukh receives a message from Pokrovsky, giving him one last chance to surrender. Just then, word comes that the second column has arrived.

Kozhukh hurriedly rides to Smolokurov and tells him his plans. He wants Smolokurov's column to attack on both flanks. Smolokurov refuses to give the order, saying that his troops are tired. Kozhukh then asks that at least they move to the station as a reserve. Again Smolokurov refuses, but changes his mind when his chief of staff politely suggests that it really wouldn't be any trouble to comply.

The attack begins. First, the inhuman roar of the artillery, followed by the living, animal roar of the Red troops pouncing on the Cossacks. The Cossacks are forced to fall back, and the Reds pursue them relentlessly for 15 versts. General Pokrovsky flees back toward Ekaterinodar with the remnants of the Cossacks and his officer batallions.

37. Kozhukh's column presses onward across the steppe, but it cannot catch up with the main Red forces who seem to be fleeing in front of them and burning the bridges as they go. Comrade Selivanov and two soldiers volunteer to take the car, break through Cossack lines, and catch up to the Reds. The car is equipped with two machine guns and takes off at top speed.

38. Selivanov and the two soldiers speed across the steppe. They pass by Cossack patrols, who don't stop them, thinking it must be a Cossack car...after all the Reds wouldn't be that foolish.

Finally, they approach the village where the main forces of the Reds have stopped for the night. Some Red cavalry men gallop out at the car and shoot at it, thinking that it must be a Cossack car. After a few tense moments, Selivanov convices the cavalrymen that they are friendly.

They are taken into the village to speak with the commander. Selivanov tells the story of their column, but the commander says he has completely contrary information. A communique from headquarters says that the band of ragamuffins crossing the mountains are fighting and killing all they meet...Cossacks, Mensheviks, and Bolsheviks. Selivanov protests. The commander agrees to send some soldiers back with him to verify his story.

39. Kozhukh and his brother are spending the night in a Cossack hut. Suddenly, a group of sailors burst in and attack them, callling them swine and smashing them with rifle butts.

Kozhukh and his brother manage to break free and run out of the hut. There, they are grabbed by a bunch of soldiers who continue the beating. But the soldiers suddenly stop and are aghast as they recognize Kozhukh. They apologize profusely. They sailors had told the soldiers that some despicable tsarist officers were staying in the hut. The sailors plotted with the soldiers, saying they would chase out the officers so that the soldiers could stab them in the back with bayonets.

The soldiers chase after the sailors, but they have already scattered.

40. Kozhukh's troops join up with the main forces. The barefoot, ragged column marches proudly in ordered ranks, looking as if they were forged from black iron. The well-fed and well-dressed main troops move around wobbily, demoralized. Kozhukh is proud of his column and delivers a rousing speech:

|

For whose sake did thousands, tens of thousands of our people suffer torture? For one thing--for the sake of the Soviet power, because it is the power of the peasants and workers. They have nothing besides that. |

Granny Gorpina gets up and announces that she's lost everything, including the samovar which was her dowry. But she would gladly do it all again for our power and our country. Granny's husband gets up and tells how they lost the horse and all the household things, but he doesn't regret it. "Long live Soviet power", he shouts. Kozhukh is picked up and carried around triumphantly.

A sailor representative gets up. He confesses the sailors' guilt before Kozhukh and begs his forgivness. Kozhukh says, let bygones be bygones, and he is tossed up in the air repeatedly in celebration.

More orators get up, declaiming what they think important. Some boast proudly about the iron discipline Kozhukh forced on them. Although no one can hear all the speeches, they all feel joyous to be part of something new, something great--Soviet Russia!