presents:

THE MAKING OF "FATE OF A MAN"

Transferring Sholokhov's story to film

by

Vladimir Monakhov

Cinematographer

M.A. Sholokhov's 107th Birthday, 24 May 2012. |

presents:

THE MAKING OF "FATE OF A MAN"

Transferring Sholokhov's story to film

by

Vladimir Monakhov

Cinematographer

from 107 Years of Sholokhov, a SovLit.net elebration in honor of

M.A. Sholokhov's 107th Birthday, 24 May 2012.

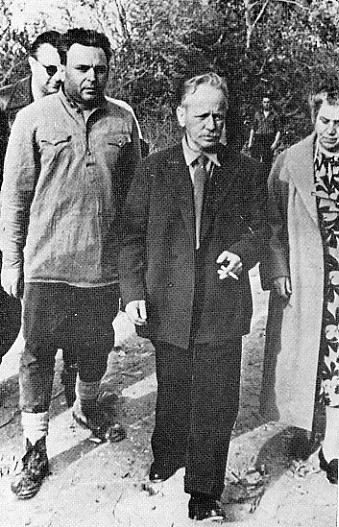

M.A. Sholokhov on the set of "The Fate of a Man", 1959 |

|

107 Years of Sholokhov |