|

| presents |

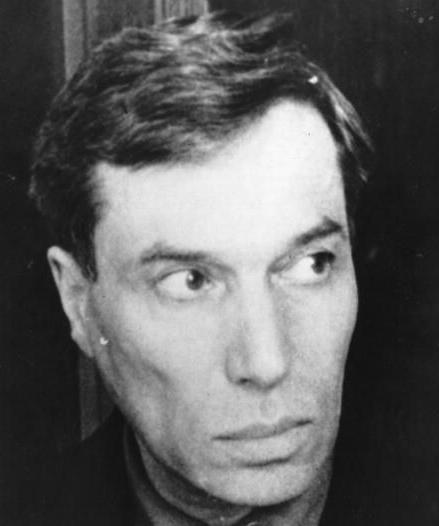

Boris Pasternak |

A Tale of Two Telegrams The Nobel Prize for Literaure, accepted and rejected |

On October 23, 1958, The Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Soviet writer Boris Pasternak "for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition."

Pasternak was pleased and flattered to win the award, and he sent the following telegram to the Nobel Foundation:

"Immensely thankful, touched, proud, astonished, abashed."

Official Soviet circles, however, were not so pleased. At the behest of the chief of the Party's Cultural Committee, Polikarpov, Konstantin Fedin came to see Pasternak at his dacha in Peredelkino. Fedin urged Pasternak to write an immediate, demonstrative refusal of the Nobel. Pasternak declined to do so, saying that nothing would make him refuse the honor; after all, he had already replied to the Nobel committee and could not appear ungrateful. Polikarpov himself was waiting at Fedin's dacha for Pasternak to appear and explain himself in person. This was another invitation, however, which Pasternak declined.

Pasternak told his son that he would willingly endure any deprivations for the honor of becoming a Nobel laureate.

Following this stubborn refusal, an anti-Pasternak press campaign began. The newspapers Pravda and Literaturnaya Gazeta lashed out at Pasternak, labeling him "a traitor", a "malicious philistine", a "slanderer", a "Judas", and an "enemy hireling". (1) There were reports of demonstrations in front of the Writers Union building, with protesters chanting, "Down with the Judas Pasternak!" A Writers Union meeting was held to consider Pasternak's fate. Pasternak did not attend the meeting, but, according to the memory of his son, the writer sent a letter in his defense, reading, in part:

"I think that one could write Doctor Zhivago while remaining a Soviet citizen, especially since it was finished after the publication of Dudintsev's Not By Bread Alone, which created the impression of a thaw. I gave the novel to an Italian Communist publisher and awaited the issuance of a censored edition in Moscow. I agreed to correct all unacceptable passages. The possibilities of a Soviet writer seemed wider to me than they are in fact. When I handed in the novel in its present form, I thought that the friendly hand of the critic would alight upon it.Pasternak, of course, was excluded from the Writers Union, although at the session where this decision was taken Konstantin Paustovsky and Veniamin Kaverin were not in attendance, and Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Ilya Ehrenburg stormed out in the middle.

"Sending my telegram of thanks to the Nobel committee, I did not think that the prize was awarded to me for this novel, but for the totality of my work, as was formulated in the proclamation of the award. I can think this since my candidacy was put forward at a time when the novel did not exist and no one knew about it.(2)

"No one can force me to refuse the honor shown to me, a contemporary writer living in Russia and, hence, a Soviet. But I am prepared to transfer the Nobel Prize money to the Committee for the Defense of Peace.

"I know that the question of my exclusion from the Writers Union will be taken up because of social pressure. I don't expect justice from you. You can shoot me, exile me, do whatever you like. I forgive you beforehand. But don't be in a hurry. This will garner you neither happiness nor praise. And remember, in a few years you'll have to rehabilitate me all the same. It's not the first time in your experience." (3)

Other pressures built up on Pasternak, most notably on his lover, Olga Ivinskaya, who suffered retaliations at her place of employment. And so, on 28 October 1958, Boris Pasternak sent a second telegram to the Nobel Committee:

"Considering the meaning this award has been given in the society to which I belong, I must refuse it. Please do not take offense at my voluntary rejection."

Years later, in his retirement, Nikta Khrushchev came to regret this whole affair with Pasternak, but claimed it wasn't his fault; after all, he hadn't even read Doctor Zhivago and was relying on the advice of others who, he claimed, misled him.

Boris Pasternak's Nobel Prize medal was finally presented to the writer's son in Stockholm, Sweden, on 9 December 1989.

1http://www.akunb.altlib.ru/CulturaLife/Exhibitions/nobel/Pasternak.html

2According to members of the Nobel Committee, Pasternak was considered for the Nobel as early as 1946.

3http://n-t.ru/nl/lt/bp.htm